Howell, 1967 —

In 1967 I was already earnestly composing for piano, trombone (my own instrument), even for orchestra. Living beside the Shiawassee River’s glacial-moraine beginnings in rural Livingston County Michigan, my best pastime was hiking along the creek’s forested banks. I was already going to Ann Arbor for trombone lessons and Youth Symphony rehearsals.

In fall 1967, after my 18th birthday, I moved to Ann Arbor and enrolled at the University of Michigan. Though not yet a music major, I began playing bass trombone in the university orchestras. For 8 years, Ann Arbor with beautiful Huron River running through it was my forested Michigan home.

The year before I was born, John Cage wrote a gentle, beautiful piece for piano, one simple enough that my 1967 piano skill could have handled. It also expressed my own urge to amble along freely improvised paths of musical exploration.

John Cage – Dream (1948)– Damian Alejandro, piano

At age 17, I never dreamed that I would meet John 24 years later (in Denton Texas of all places), a gentle soul who loved mushrooms. And I had yet to discover this piece or any John Cage music. But I was also writing simple and (I thought) beautiful piano music.

Two pieces for piano that expressed my attitude of wonder while wandering in the woods were updated fifty years later with my 2023 editing skills. “Mystic Breeze” and “Light” were my 12th and 18th completed TC compositions. “Riverbank” is from a 1967 sketch of an “interlude” for trombone and piano.

They make a nice set of three, revealing that before formal study my compositional explorations were already discovering more exotic harmonies and rhapsodic forms resembling Debussy’s Impressionism and even the post-tonal possibilities of 12-tone rows.

ARBOR SKETCHES

Clark 1967 (TC-12/18)

- 1. Breeze

- 2. Riverbank

- 3. Light

Brno

Twenty-four years later in 1991, I was invited to perform at the 26th Brno International Music Festival. It would lead me on a path of musical and cultural exploration that has filled my life since with beauty. (I had also married a beautiful Czech-American woman in 1976.)

Brno is the capital of the Moravian province of what was then Czechoslovakia. Brno was the home city of the great 20th-century Moravian composer, Leoš Janáček. After visiting his home and school in Brno and his summer home in Hukvaldy, I began to study his music.

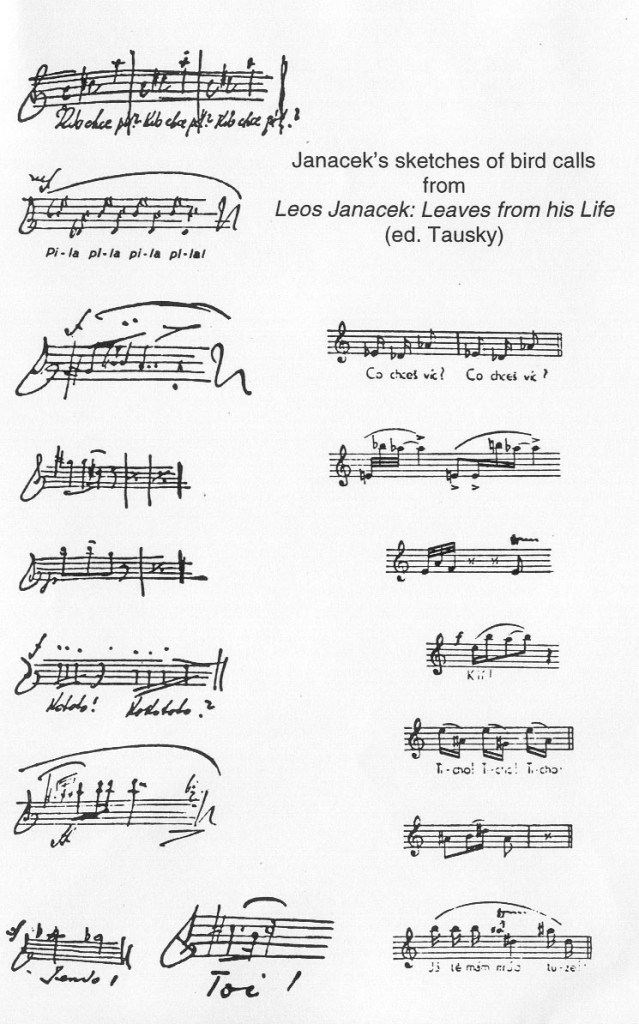

Two things captured my interest. Like Bartok, he embraced and collected the folk music of his homeland. He also exalted in nature, walking around the wooded hills of Hukvaldy’s castle ruins, and collected his own transcriptions of bird calls.

While there on the first visit, I was commissioned to compose a ballet for the local dance theatre company. Inspired by Janáček’s birds, I began to write my own music for what would become the ballet, PTACí (“Birds”).

Lesní cesty

In a music store in Brno, I also discovered his marvelous 1911 set of piano pieces, the title of which translates “On the Overgrown Path.” On a return trip, I was able to visit the Moravian Music Archives in Brno to examine his original hand-written manuscript of the pieces.

Excerpted from Series I:

- No. 5, They Chattered Like Swallows

- No. 6, Words Fail!

- No. 7, Good Night!

- No. 8, Unutterable Anguish

- No. 9, In Tears

- No. 10, The Barn Owl Has Not Flown Away!