Canon is a venerable, centuries-old compositional device, building counterpoint between a melodic line and one or more delayed and possibly transposed echoes of itself. It seems like a magic trick, with the effect of a strongly cohesive contrapuntal texture of independent lines that are like-character clones of each other. Canon is more intense than a fugue, which formalizes the echo cloning technique interspersed with free counterpoint.

1. Study historical models

There are many great models to study. Many 16th-century composers (notably Josquin and di Lasso) wrote canonic choral mass movements. Known more for his fugues, the great 18th-century contrapuntal master, Bach, also wrote several intriguing canons in his late work The Musical Offering. No more elegant model exists than the first movement of Anton Webern’s Symphonie Op. 21 (1928), in which four voices are spun out by successions of instruments each in turn differently coloring two to four notes of the same 12-tone line.

Like every fine magic trick, there are several basic techniques we can learn to construct a canon. I’ll cover three, which I will call Zigzag technique, Trial-and-error technique, Rhythmic alternation, and Stretto echo.

In 1610, Venetian composer Diruta wrote Il Transilvano analyzed Renaissance polyphonic style by codifying five species of rhythmic relationships between contrapuntal lines. Johann Joseph Fux, in his monumental 1725 pedagogy, Gradus ad Parnassum, explicated 16th-century counterpoint using these rhythmic species, of which the following are of special importance for us in this lab:

- FIRST Species – note against note

- FOURTH Species – lines alternating, seldom moving simultaneously

- FIFTH Species – a mixture of rhythmic values in all lines

2. Zigzag

My name for it says it simply, like laying bricks one at a time but staggered to overlap.

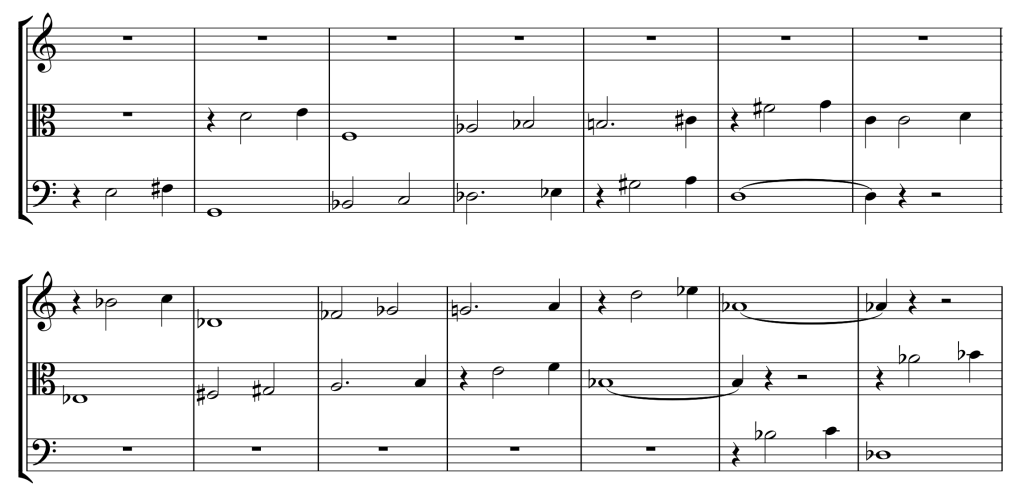

- Compose a few notes of the lead line. (In the example below, it is just three notes in two measures.)

- ZIG: Establish a time delay. (in the example, one measure of two half-note beats). Duplicate the first notes (rhythm and melodic interval shape) in the following line, starting on a chosen pitch that makes the kind of vertical contrapuntal interval you desire to emphasize.

- ZAG: Select new notes for the lead line that overlap with the ZIG notes, again making your desired vertical contrapuntal intervals. These ZAG notes need not match one-to-one the rhythms of the ZIG notes, providing the opportunity if desired to establish a Fifth-species rhythmic mixture.

- The notes of this ZAG now ZIG into the following line, preserving the same transpositional level you established in the first ZIG.

- Keep going as long as you wish or have stamina for. When ready to cadence, arrive at a longer note of stable pitch-sense in the lead line.

The canonic material you just contructed can be reused transposed. Just be sure you transpose all lines together by the same transpositional interval.

In the example below, my seven zigzag-composed measures are transposed down one semitone.

Starting on Eb might be useful to follow the first statement of the material, which ended on D in the lead (lower) line. Or I could transpose the whole thing up 8 semitones to start on C, eliding with the middle C (bass clef) that ended the following line.

Adding the third part enables this stair-step sequential transposition of the two-voice canon to go on and on . . .

3. Trial and error

Let’s try a different technique to add a canonic answer, one that is facilitated by notation software such as Finale or Sibelius. This way involves

- copy the whole lead line, not just a head motive

- choose a time delay or maintain one already established. Paste into the new answering voice the lead line

- Playback the synthesized audio to test aurally for contrapuntal viability.

- If it sounds bad, analyze the vertical intervals to discover why.

- Make a strategic choice of a transposition of the pasted-in answer, then test it aurally.

- Keep trying different transpositions until you find one you really like.

For traditional diatonic tonal subjects, common transpositional choices are: unison; octave; Perfect 5th (7 semitones); Perfect 4th (5 semitones).

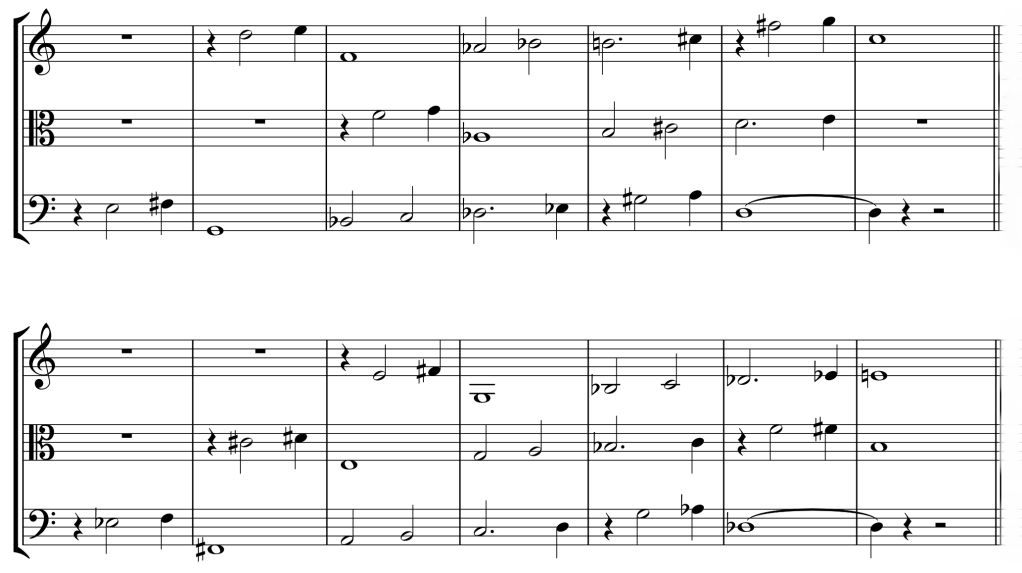

In the following examples, I show in the first system a trial of an added third voice in the middle, starting on E (alto clef) transposed an octave up from the lead. For the second system, I tried adding a third voice on top, transposed up a Major 9th (14 semitones) from the lead’s start on Eb to start on F (treble clef).

Horrible, yes? Why? What vertical contrapuntal invervals are the sour ones to your ear?

I’ll jump to a better trial that succeeds in both places.

In this successful trial, the first system’s added middle voice transposes from the lead’s E up 13 semitones (minor 9th), and later in the second system the added upper voice transposes up also 13 semitones from the lead’s Eb to a second answer starting on E. The minor 9th is unusual, unorthodox, chromatic, not a solution we might predict . . . but it works!

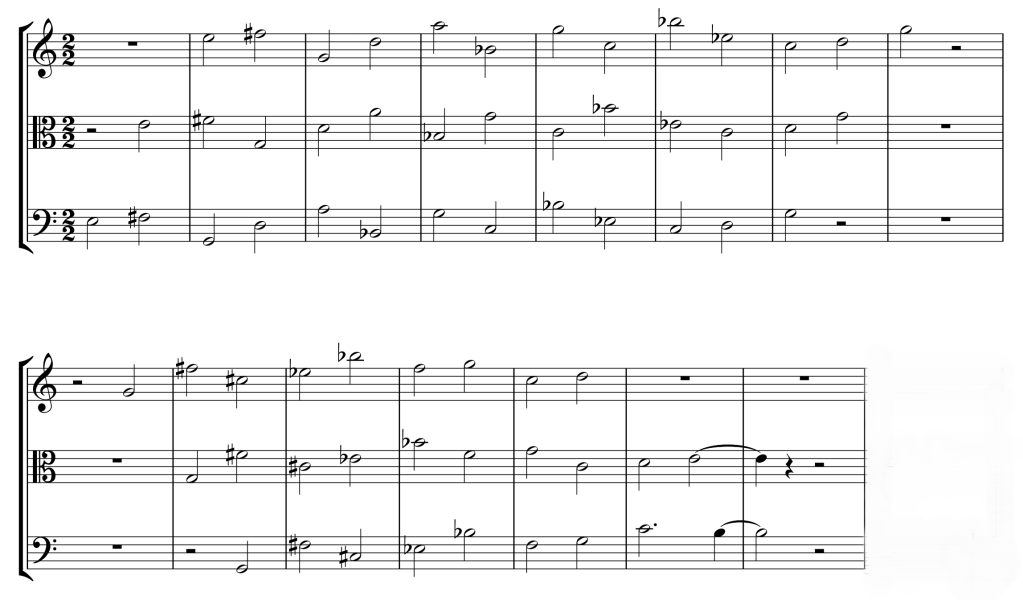

4. Rhythmic alternation

This will be like Fux’s Fourth Species. The lead subject is best with some long note values, leaving ample time for answering voices to present pitches when it is not moving. Transpositional choices for entering answers become fixed as predominant vertical intervals throughout the canon. In this example, the first answer chooses down 11 semitones plus an octave, and the second answer enters up 7 semitones (Perfect 5th) from the first answer, which is down a Major 10th (14 semitones) from the lead line. Thus vertical (harmonic) intervals of 11, 7, and 14 semitones end up projecting harmonies based on the 7 4 array: G up 7 to D up 4 to F#, which is up 11 from G. That sets the harmonic character of pitch constellations throughout the canon.

5. Stretto echo

Stretto is the term used in fugue structure for when an answer to the subject happens before the subject is finished, sometimes with a delay as short as only one or two beats. For a canon, this offers an interesting strategy for choosing pitches to shape a subject that makes its own arpeggiated harmony as it goes. The answers at unison (not transposed) are literally echoes. Even with answers octave-transposed, the effect is a multivoice arpeggiation. The fascinating wrinkle, however, is that the “chord” being arpeggiated is constantly evolving, dropping one pitch and adding one new at each note of the lead line.

Though this setup can work with other rhythmic “species” of lines, it is particularly interesting in note-against-note First Species conforming rhythms.

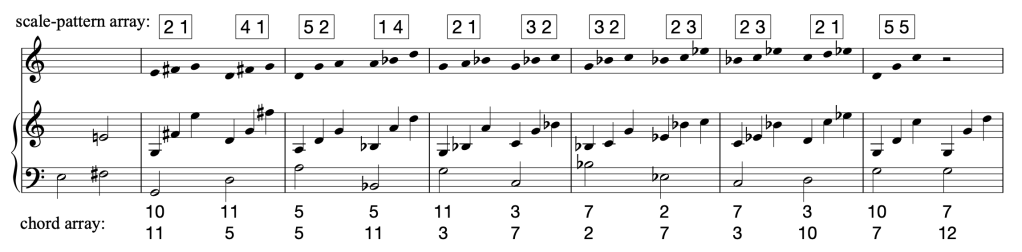

Here is how it can work, using the canon above as a straightforward example.

This analysis sounds as a rather nice progression of arpeggiated chords and simple flute line! The important point, though, is that this progression did not come first. It was built by the canonic subject line as each new pitch was chosen to make a certain array with the previous two pitches in an ongoing, evolving flow. Magic!

6. Spin a piece

For our example, we’ll follow the order of the example techniques:

- two-voice zigzag canon

- add a third voice by trial and error

- stretto echo of the same subject

- Rhythmically spacious subject allowing non-synchronous timing of answers

- Recapitulation of the stretto echo canon

The result is a fuller working out of No. 10 of the 14 specimens in my Book of Canons:

Black Canyon

The title comes from my photographic memories of the Black Canyon of the Gunnison River, named for the ever-present shadows the narrow canyon’s steep, sheer, tall rock walls cast on the river flowing far below. The sheer cliffs of the Black Canyon are metamorphic Precambrian gneiss and schist, streaked with thin, brighter-colored layers of pegmatite. These streaks sketched on the darker rock look like maps of ancient contrapuntal lines.