Unaccompanied instrumental solos go back at least to the 18th Century, such as Bach’s famous violin partitas and cello suites. In the late 19th century, Debussy’s Syrinx for solo flute met the challenge of making a piece with just one wind instrument, not capable of the double-stops that complicate the rich textures of Bach’s string writing.

1. Choose a model

Syrinx launched a whole genre of unaccompanied flute solos, with Density 21.5 (1927) by Edgard Varèse and Sequenza (1958) by Luciano Berio leading the way to experimentation with virtually every wind instrument. My Night Songs (1969) for solo trombone is very much within the tradition of this genre. As a trombonist and undergraduate composition student, I used my intimate knowledge of the instrument to select gestures and techniques to experiment with compositionally.

2. Choose an instrument

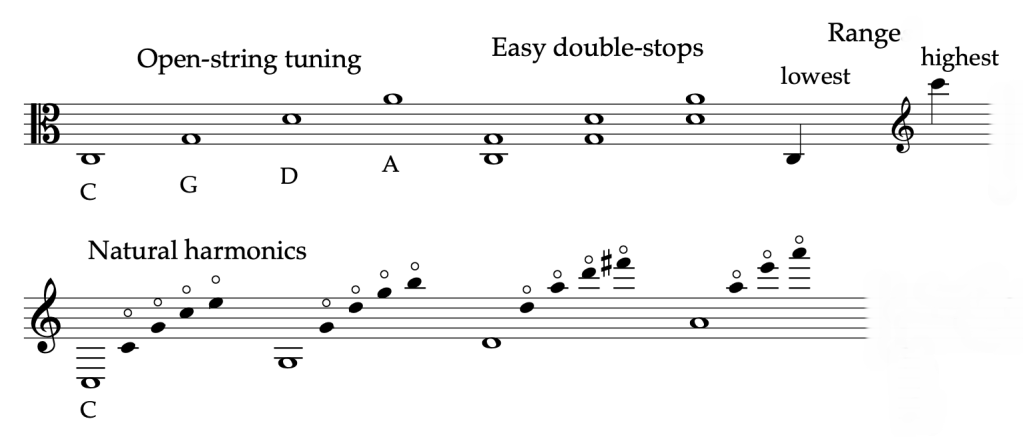

I also love the viola, so I readily agreed to write an unaccompanied solo for each member of the Pleasant Street Players, including violist Ames Asbell.

3. Sketch idiomatic gestures

Before I Sleep is inspired by a famous, beautiful Robert Frost poem, “Stopping By Woods.” Its snowy scene tempted me to quote a Mahler’s Symphony No. 4 (1900) that starts with sleigh bells and flutes doing something like the A gesture. (Sul ponticello is a special string technique to brighten tone by moving the bow closer than normal to the bridge.)

B features the quick scale patterns so indigenous to orchestral strings.

C uses a mute, attached to the bridge to subdue the tone. It also uses double-stops, drawing the bow across two adjacent strings together, making two-pitch diads and even two-voice counterpoint. These use an open string and the next string a perfect-fifth higher or fingering a pitch more than a perfect-fifth higher.

D makes bird-like trills.

E uses sul tasto, the reverse effect of sul pont, drawing the bow closer to or over the fingerboard for a darker, warmer sound.

F makes the high, glass-like sounds of natural harmonics, produced by touching a string lightly at one of its partial-vibration nodes while drawing the bow on it. (harmonics, like open strings, have no vibrato. Sorry my synthesizer insists on applying vibrato anyway.)

G is a very special effect used by George Crumb in his early chamber music. Sometimes called a seagull effect, it produces a quick arpeggiated succession of natural harmonics by running a finger lightly up and down across the partial-vibration nodes of the string.

The gestures sketched above show a wide variety of pace and rhythmic characters.

4. Interval language

The B idea is scalar, running around through an unusual scale. It is almost an octatonic wholetone-halftone scale, but modified by an Ab, making the lower tetrachord the start of a Phrygian mode scale.

For the rising and falling landscape of melodic lines, choice of pitches and the cumulative constellations they form can be freely crafted the old fashioned way, plunking out pitches on a piano (or on the actual instrument of the piece) in a trial-and-error search for pleasing pitch streams. Identifying one’s favorite intervals can lead to using a more organized cell approach as described in MtMM Part II.

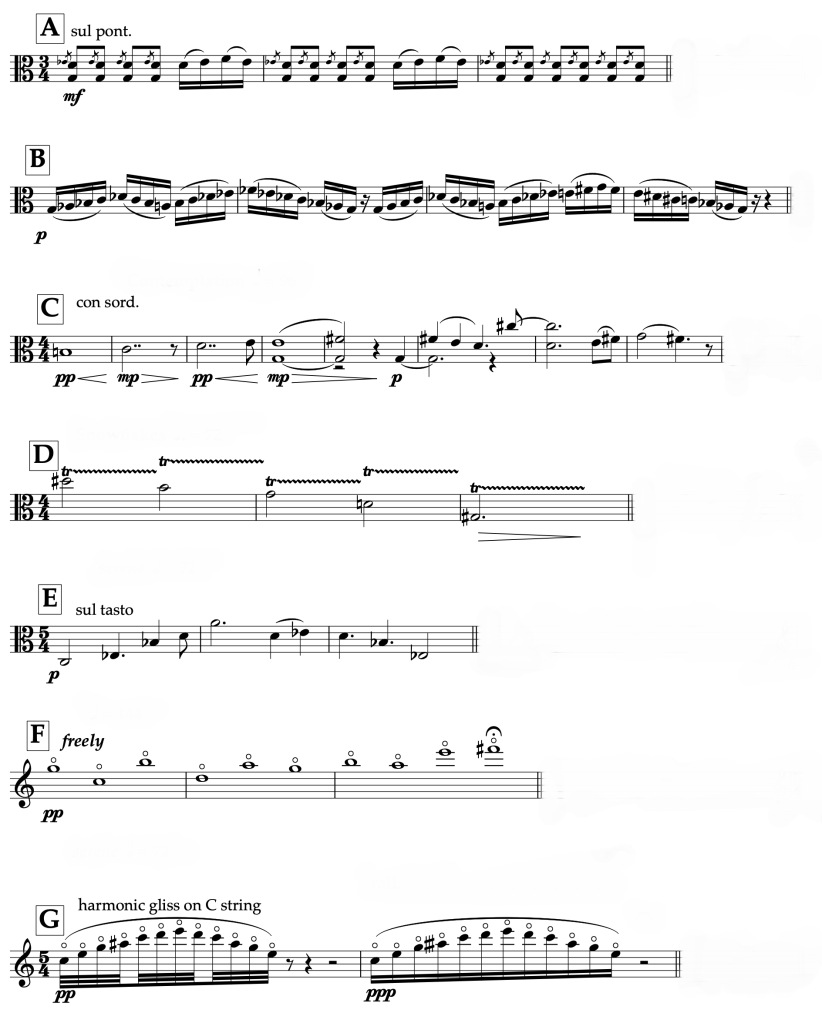

In the TC example, an interesting constellation is established and simply arpeggiated in various shapes.

This produces a single, stable harmonic prolongation, a calming stasis in which the line keeps retracing recently touched pitches.

5. Edit the notation

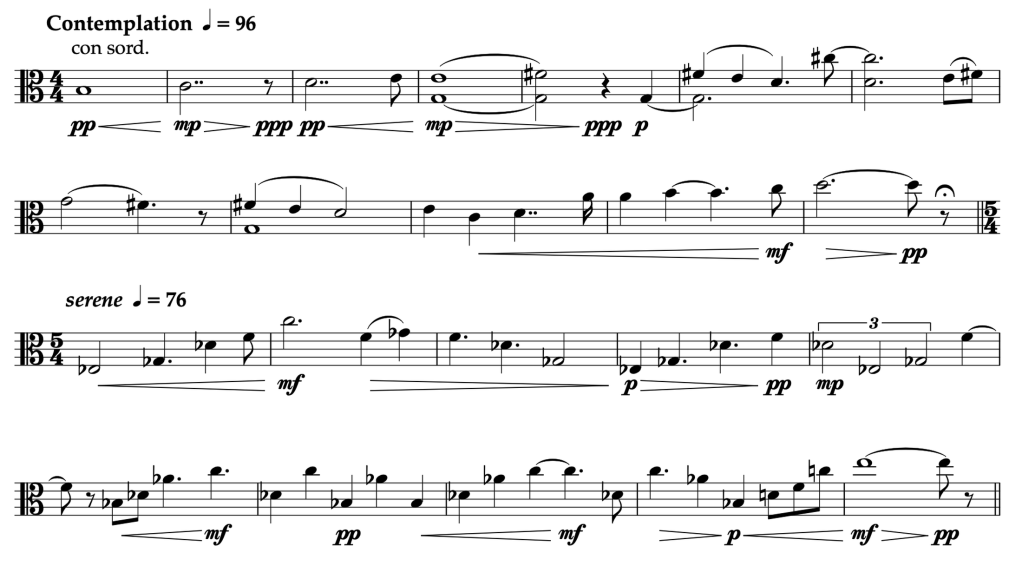

The score is not finished until all details are included, showing clear information and intent. A solo line especially needs strong dynamic shaping to be interesting as a solitary musical voice. The following example from the viola solo notates many of the necessities on this checklist:

- timing information, including tempo, rallentando, fermata

- expressive indications

- dynamics, including ample changes, crescendos, diminuendos

- phrasing such as slurs

- special techniques such as con sordino, sul pont, sul tasto, harmonics

6. Overall form

An unaccompanied solo is a soliloquy. The dramatic tone can vary: a rage; a contemplation; or a story. The form can be a continuous flow of development of a single, persistent gesture, as in Berio’s Sequenza series. Or it can be sectional, a story told in short chapters, a poem divided into stanzas.

The TC example, actually a previously composed 2018 piece titled Before I Sleep, was written for my colleague Ames Asbell of the Texas State music faculty and Pleasant Street Players, an outstanding artist and player of one of my favorite instruments. The title is a quote from the last lines of Robert Frost’s famous poem “Stopping by Woods,” a contemplation of death on a nocturnal sleigh ride in the snow. The lead motive is a quote from Mahler’s Symphony No. 4, which open with flutes and sleigh bells jingling what is called the “bell theme.” My musical form follows the poem, in three sections:

- sleigh bells and a trotting horse (gestures A and B)

- snowflakes (a variation of B transitioning into D and F)

- contemplation (C and E)

The poem ends famously with a direct repetition of the last line, “and miles to go before I sleep.” That could have been the going-to-sleep hypnotic musical ending as well, but the poet is not ready to die. My musical ending instead is not a coda but a brief tag, gesture G, the horse gently shaking his bells in the glistening moonlight.

Before I Sleep