1. Establish models

In 1973, I composed my second orchestra piece as a graduate student at the University of Michigan. The title was inspired by John Cage’s famous Imaginary Landscapes No. 4, which we performed as I was an ensemble member of Contemporary Directions. The idea of animating an otherwise static sound mass, devoid of progressive harmony, was a quintessential feature of what I came to think of as the Midwestern Style of 1960s and 1970s large ensemble music. Successful models included prize winning pieces such as (my teacher) Leslie Bassett’s Variations for Orchestra (1966), Donald Erb’s The Seventh Trumpet (1969), and Joseph Schwantner’s …and the mountains rising nowhere (1977) and Aftertones of Infinity (1979).

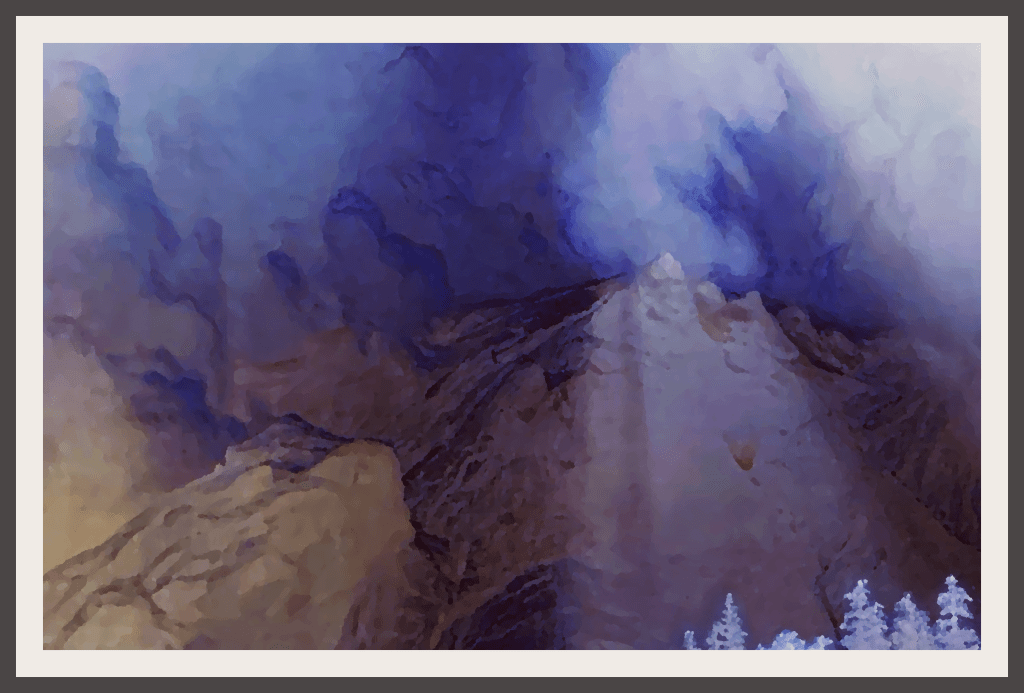

So many great American landscape artists of the 19th century painted fascinating panoramic scenes. One of my favorites, who captured the grandeur of Western, mountainous landscapes, was Albert Bierstadt:

Albert Bierstadt: Passing Storm over the Sierra Nevadas (1870) – San Antonio Museum of Art

You can see stark contrasts in brightness and in sense of motion between the mirror-smooth water and roiling clouds. Even the word “passing” in the title suggests change, a necessary ingredient of an analog musical landscape.

2. Build big constellations

The fixed, stationary nature of a landscape painting suggests a static harmonic approach, projecting and prolonging one constellation as an underlying sonority for the whole musical “canvas.”

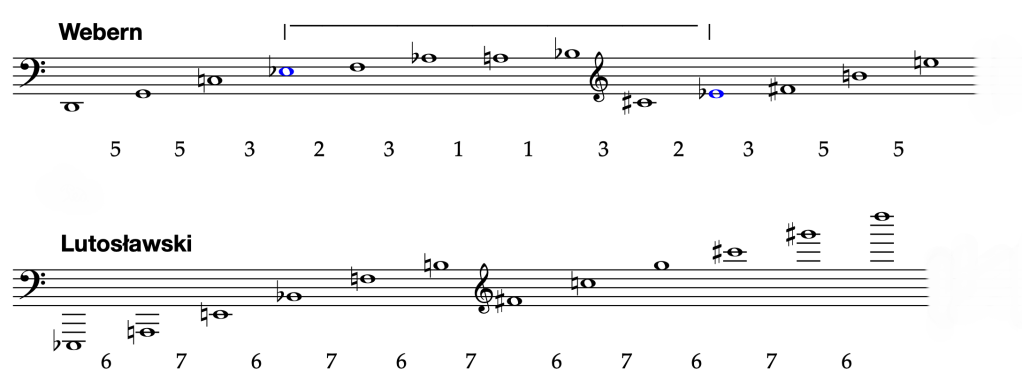

Here are two examples of a 12-tone constellation. The first was used as the underlying sonority of the pointillistic first movement of Anton Webern’s Symphonie Op. 21 (1929). Note that to accomplish the palindromic symmetry of the interval array, Eb is placed in two different octaves, thus 13 pitches total.

Another example of placing all 12 pitch classes in particular octaves is from Witold Lutosławski’s Jeux vénitiens (1961):

TC example

A large register-spanning constellation need not be 12-tone. Building a sonority of very different (less dissonant) quality, let’s start with just octave C’s and their fifths, G. Pitches a whole step away from these tonal pillars are added. The result is 13 pitches only from the F major scale. Then their complement, a big 8-pitch constellation of similar array, is built from the pentatonic scale of the flats, the other “black keys” .

3. Animations

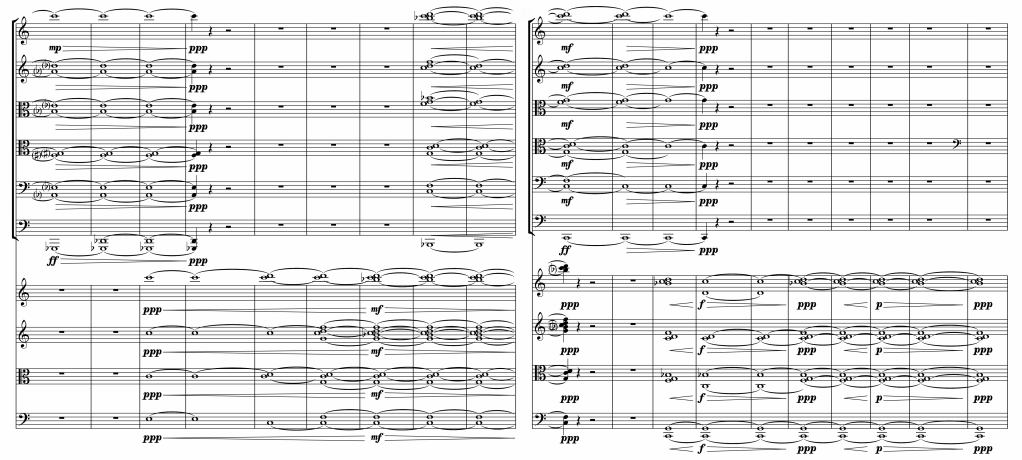

Different basic techniques for animating in time a large constellation of pitches . . .

Arpeggio – one note at a time in any order, is a kind of stacking.

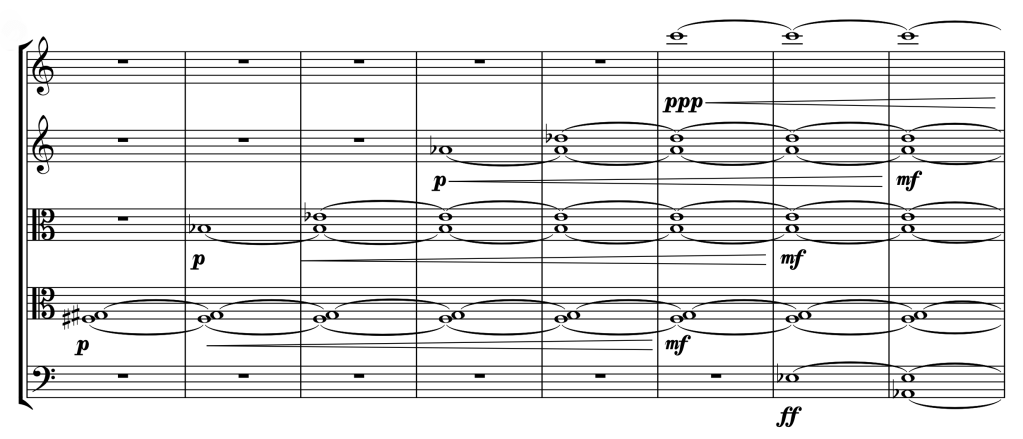

Stacking – introduce sustained tones one or two at a time. The reverse, unstacking, works too.

Swells – crescendo/diminuendo the whole sonority (think ocean waves in Debussy’s La Mer)

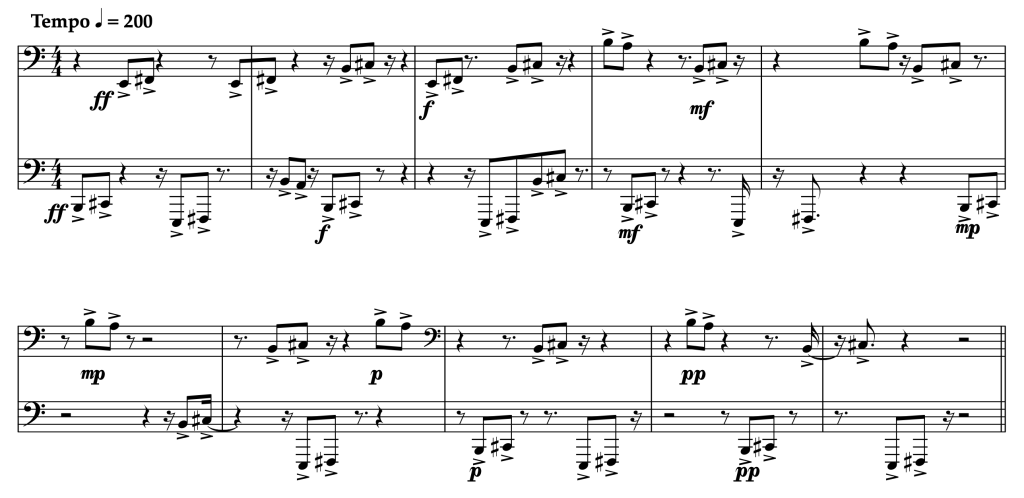

Pointillism – a more complex texture of distinct sound points separated by registral and rhythmic spacing. Although they can be different sound colors, in this example they are all the same timbre:

4. Develop a sound palette

Larger ensembles can be good for musical landscapes, offering a varied palette of instrumental timbres. Like pigments, these sound colors group in hues: the

- double reeds

- other woodwinds

- cylindrical brass (trumpet, trombone)

- conical brass (horn, euphonium, tuba)

- bowed strings

- plucked strings (harp)

- metal pitched percussion

- wood percussion; drums; exotic gongs, etc.

For synthesized sounds, beyond emulating these instrumental timbres, envelope and spectrum distinguish the sounds:

- sharply accented or gradually emerging sound onset

- bright metallic to dark hums

- reverberation.

For Passing Storm, I chose three “choirs” with distinct sound qualities:

- Clanging percussion and plucky harp

- Gentler emerging-onset sounds (Sibelius Pad 2 – warm) functioning like woodwinds

- Brighter sustained sounds (Sibelius FX4 – atmosphere) in the orchestral role of bowed strings

5. Compose the whole canvas

In painting, “composition” refers to the main parts of an image and how they are arranged with each other in two-dimensional and the illusion of three-dimensional space. For music, we might call this the macro form. As with most landscape paintings, the musical textures may overlap in continuous sound. There may be sectional divisions, analogous to strong demarcation lines like a horizon. The sense of broad, distant scale of view will be best captured with extended textures of expansive rhythm and even with reverberation.

While not trying to actually map the physical composition of a painting, we can get musical inspiration from considering the painting’s features of background, foreground, and highlights of strong visual focus. My example was coming together starting with distant swelling sonorities, which as they crescendo feel like they are emerging forward toward us.

After deciding to name the piece Passing Storm after the Bierstadt painting, however, I realized I had no storm in the music, just gentle sprinkles. Thus was created a stronger sonic rendering of the sprinkles to provide a more aggressive introduction. The proceeding four minutes overlaps sound masses exhibiting the various animations in time we explored earlier. Dark and light in a painting are portrayed by loud and soft, timeless sustained sound vs. busy points of sound.

Animated Landscape No. 4: Passing Storm