a composer’s journal

Part 3

CONTENTS

The journal retrospectively logs places, events, ideas, and sounds of a life of composing. Each chapter remembers a time and place in my career, and explores a particular compositional design approach derived from my study of 20th-century masterworks. Audio clips offer listening to all pieces cited, both the masterworks and my later compositions inspired by them. Take some time to listen as well as read!

Part 1 CONTENTS

Part 2 CONTENTS

21. Constellations

Texas Hill Country, 2021

Retiring as a music school executive at the onset of the Covid pandemic in 2020, I started putting together a book. I have long been deeply interested in science, especially astronomy. Having read a great deal of general science writing, I discovered ground-breaking pioneers who had methodically and comprehensively mapped the possibilities of their particular field — cartography, astronomy, chemistry, even the exploration journals of Lewis and Clark’s great expedition. Inspired by them, my music-mapping Periodicity Project began in 2021 as a comprehensive catalog of musical patterns and processes, meant to provide simple tools for understanding the complexities of modern music. It grew into a book, Mapping the Music Universe, written for anyone curious about how music works, especially in the 20th-21st-century modern and post-modern eras. Currently under review for university press publication, it is my exploration of how some less traveled conceptual paths lead to musically interesting creative possibilities.

Mapping the Cosmos

Along the way, Mapping the Music Universe produced several small etudes to illustrate the compositional potential of musical patterns explained in the book. The inspiration to collect them into a series came from many years of fascination with Bartók’s wonderful Mikrokosmos series of piano pieces in modern styles. Here are two of my favorites to play and to teach:

Lajos Kertész, piano

Lajos Kertész, piano

Book I of my Mapping the Cosmos contained seven etudes originally sketched for piano. The five in Book II were adapted from more complex textures. The seven of Book I are simpler, each etude titled with an astronomical entity named for a mythological character.

Here are four from Book I that are named for constellations.

Pisces – The Fish; 12th constellation of the Zodiac

Cygnus – The Swan; a northern constellation

Pleiades – Seven Daughters of sea-nymph Pleione; an open star cluster

Scorpius – The Scorpion; 8th constellation of the Zodiac

Here are all seven in more colorful sound synthesis:

Mapping the Cosmos – Book I

Clark 2023 (TC-114)

all seven synthesized

Cassiopeia

In Journal episode 9, I described a compositional process I began exploring in the 1980s. Inspired by Larry Austin’s groundbreaking Canadian Coastlines, I began tracing natural patterns onto graph paper. Particular points on the graph yielded 2-dimensional coordinate values that could be interpreted as timing and pitch information. The first patterns were shorelines, making the initial sketches for PENINSULA (1984, TC-50).

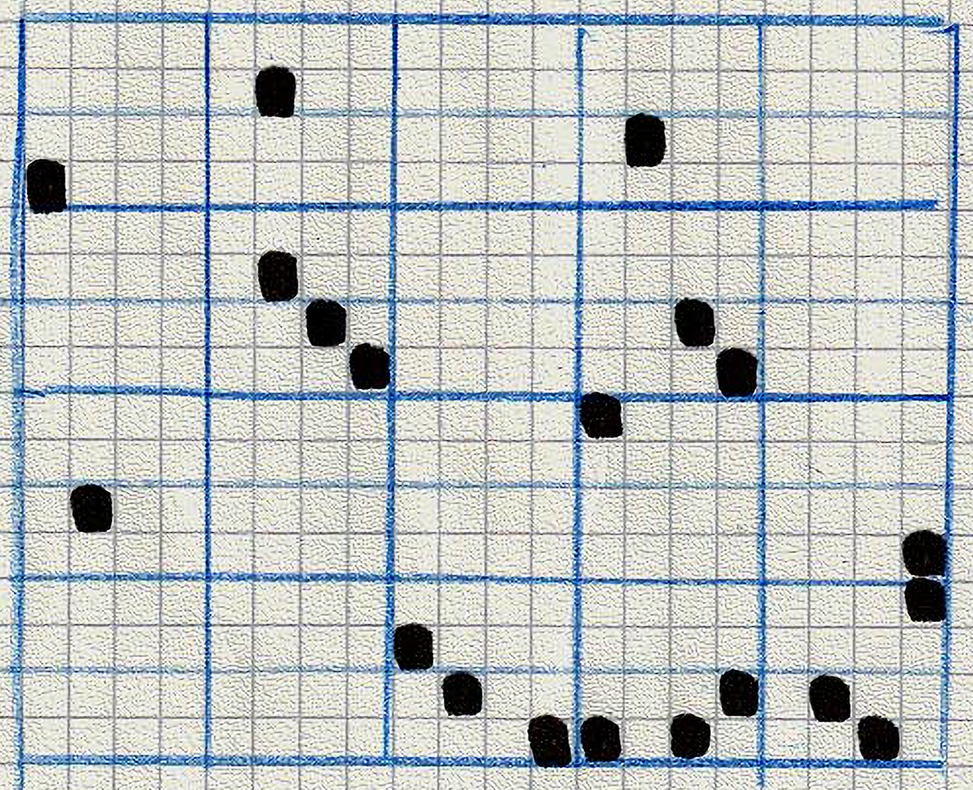

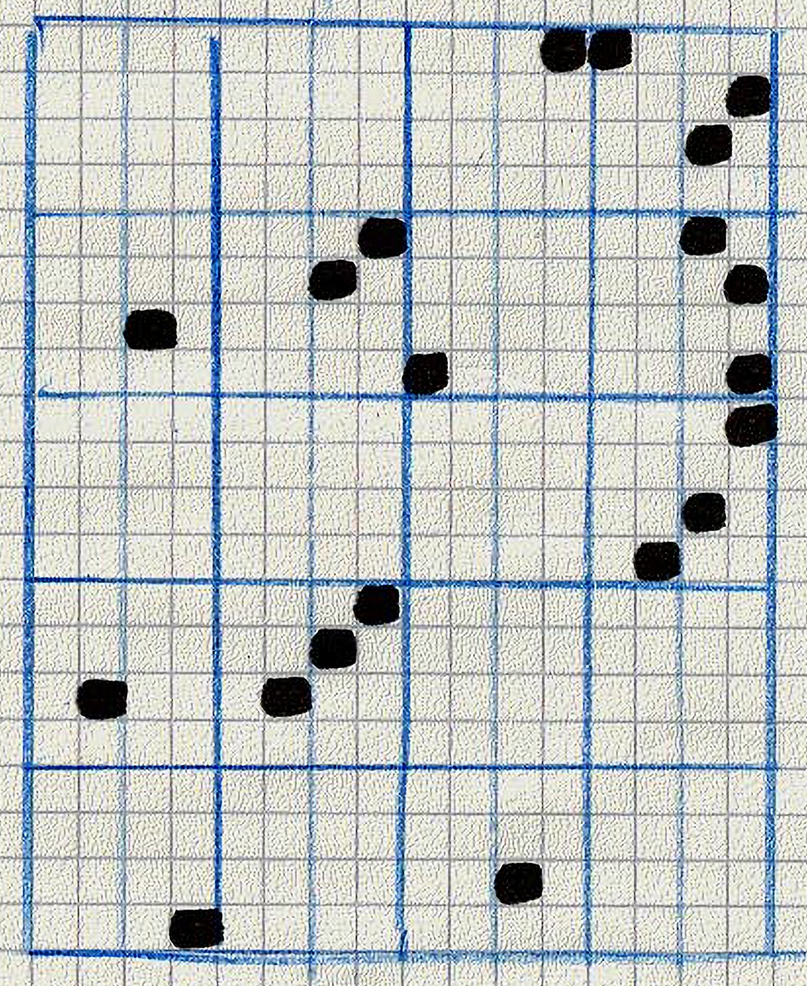

Having always been interested in astronomy, I then tried plotting star constellations on two-dimensional matrix graphs. The coordinates of each star in a constellation could be interpreted as time-point and pitch information, resulting in a complex arpeggiated group of notes. More intriguing was the capability to rotate the map, resulting in many possible variants that stretch or compress the rhythm and chord structure.

The first compositional product of the star map work, LIGHTFORMS 1 – Constellations (TC-65), scored for piano, was published by Borik Press in 1992. Naming these patterns, pitch-time chord arpeggios, as constellations became a breakthrough concept.

Arvo Pärt: Für Alina (1976)

The constellation Cassiopeia in the northern sky is named after the vain queen Cassiopeia, mother of Andromeda in Greek mythology. One of 48 constellations listed by the ancient astronomer Ptolemy, its distinctive ‘W‘ shape is formed by five bright stars. Cassiopeia contains some of the most luminous stars known, including three hypergiants. Its brightest star, Cassiopeia A (“Schedar”), is a supernova remnant and bright radio source.

The music arose from tracing a map of its brightest points of light. The coordinates of these points on a two-dimensional graph were converted into time and pitch patterns articulating a grand sonority. The graph can be rotated, kaleidoscopically transforming the pattern into similar sonorities.

PERSEUS

CASSIOPEIA

CEPHEUS

ROTATED 90 degrees

The same treatment applied to Cassiopeia’s constellation neighbors Perseus and Cepheus builds a denser field of sounds. All this elaborate graphing and plotting may seem too complex and too abstract. The process, however, resulted in an intentionally abstract musical experience that metaphorically echoes the awe of viewing the brilliant star-studded dark sky through a powerful telescope.

CASSIOPEIA

Clark 2025 (TC-157)