Leelanau, 1983 —

My last summer working at what was then called the National Music Camp in Interlochen, Michigan was 1983. We spent as much time off as possible on the nearby shore of Lake Michigan. Three spots on the western edge of the Leelanau peninsula were favorite magical places. Otter Creek played out into a sandy delta at the beach, perfect for a picnic. Good Harbor Bay was an excellent shore for finding gray Petoskey stones, revealing fascinating hexagonal-shaped fossils when wet. Farther north, the Great Sleeping Bear Sand Dunes rise majestically hundreds of feet above the water’s edge.

Béla Viktor János Bartók’s monumental 1937 work, Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste, begins with a mysterious, meandering line played by subdued violas. It sounds to me like walking at the water’s curving edge on a fog-shrouded beach. The line becomes the subject of a gigantic fugue, building to a powerful climax. In my imagination, we reach the sheer cliff of a massive bluff at the end of a Lake Michigan bay.

Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste

Chicago Symphony

LISTEN > YouTube

Shores

Of course, Bartók never saw Lake Michigan. But shorelines are a fascinating kind of fractal patterns in nature.

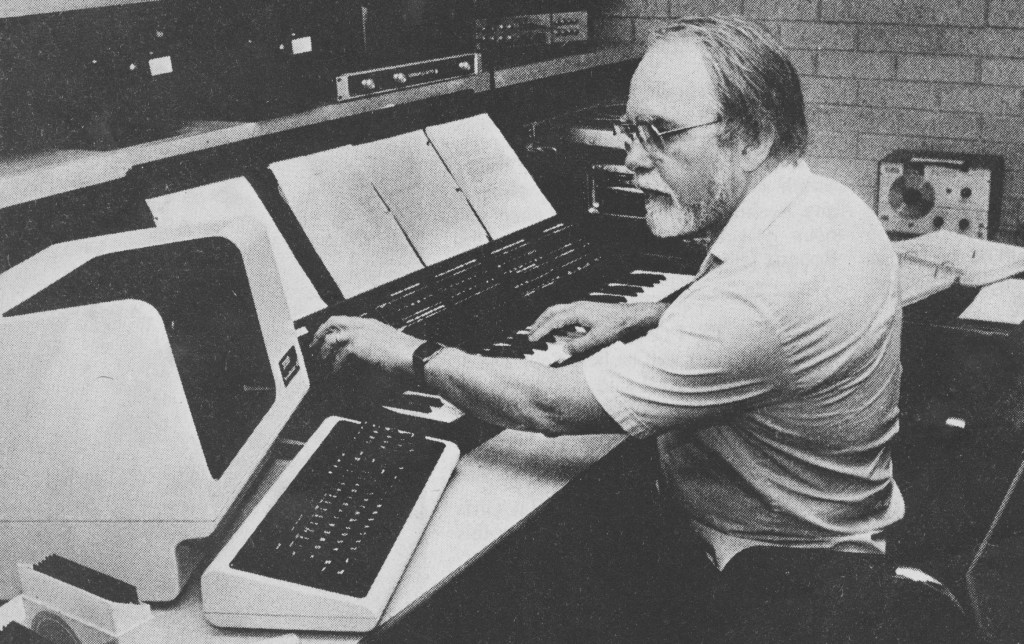

In 1980, Larry Austin received a commission from the Canadian Broadcasting System and KPFA for an experimental radiophonic work. For the premiere broadcast, the performers were in three different Canadian cities, synchronized by electronic signals! The mind-boggling result was a piece consisting of

“a massively contrapuntal texture, with many instruments playing continuous, independent lines, all in different, independent tempos. The contours of each contrapuntal part were determined using maps of Canadian coastlines.”

[Clark — Larry Austin: Life and Works of an Experimental composer. Borik Press, 2012, p. 40]

I.C.M.C. 1981, Denton Texas

LISTEN › YouTube

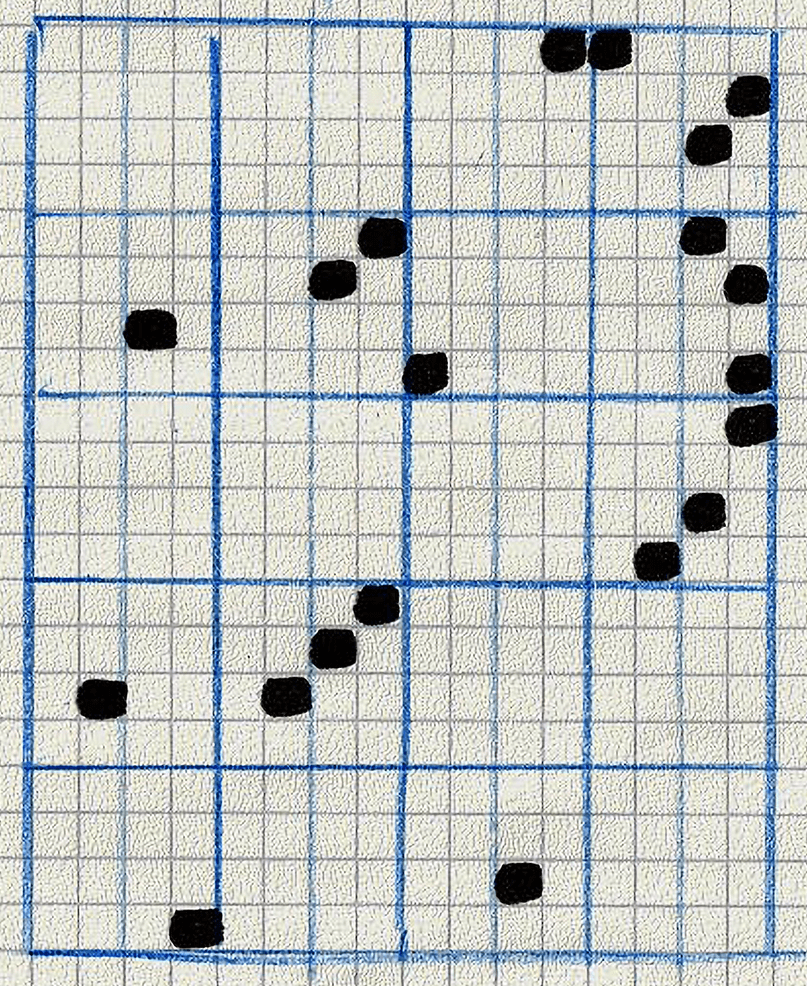

Glacially-etched shorelines also inspired sonic imagery for a series of my pieces culminating in PENINSULA. Mappings of the natural contours of the Leelanau Peninsula provided richly varied patterns as basic coordinate numbers for sculpting sound patterns. The piano explores some of the endless possibilities for articulating a spectrum of sonorities. A surrounding environment of synthetic sounds was made by digitally analyzing timbral qualities of acoustic instruments, mostly with percussive articulations (metaphorically the rocky shore). The timbres were modified and resynthesized into a pointillistic sound texture. The density of the sound events rises and falls in waves according to changing values derived from the basic mappings. Larger confluences of waves are located in time by map points of special significance on the graph.

The coexistence of piano sonorities and synthetic sounds is a metaphorical meeting of seascape and landscape, both animated in time.

PENINSULA

Clark 1984 (TC-50) Borik Press

Clifton Matthews, piano, Winston-Salem NC, Feb. 2007

There were many other groundbreaking pieces by my late friend and collaborator, Larry Austin. The first, Improvisations for Orchestra and Jazz Soloists, brought him to national prominence in 1964 with highly publicized broadcast performances by Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic.

As Austin moved into computer music, he began exploring compositional algorithms using mathematical models such as fractals.

Some of Charles Ives’ sketches for his monumental, never completed Universe Symphony were tracings of the outlines of rock formations. Austin studied deeply this Ives work starting in 1974 and eventually completed a version of Universe Symphony for expanded orchestras in 1993. In Austin’s own work beginning in 1976, mapping contours of mountain ridges and star constellations yielded musical patterns for First Fantasy on Ives’ Universe Symphony, Maroon Bells, and *Stars.

Constellations

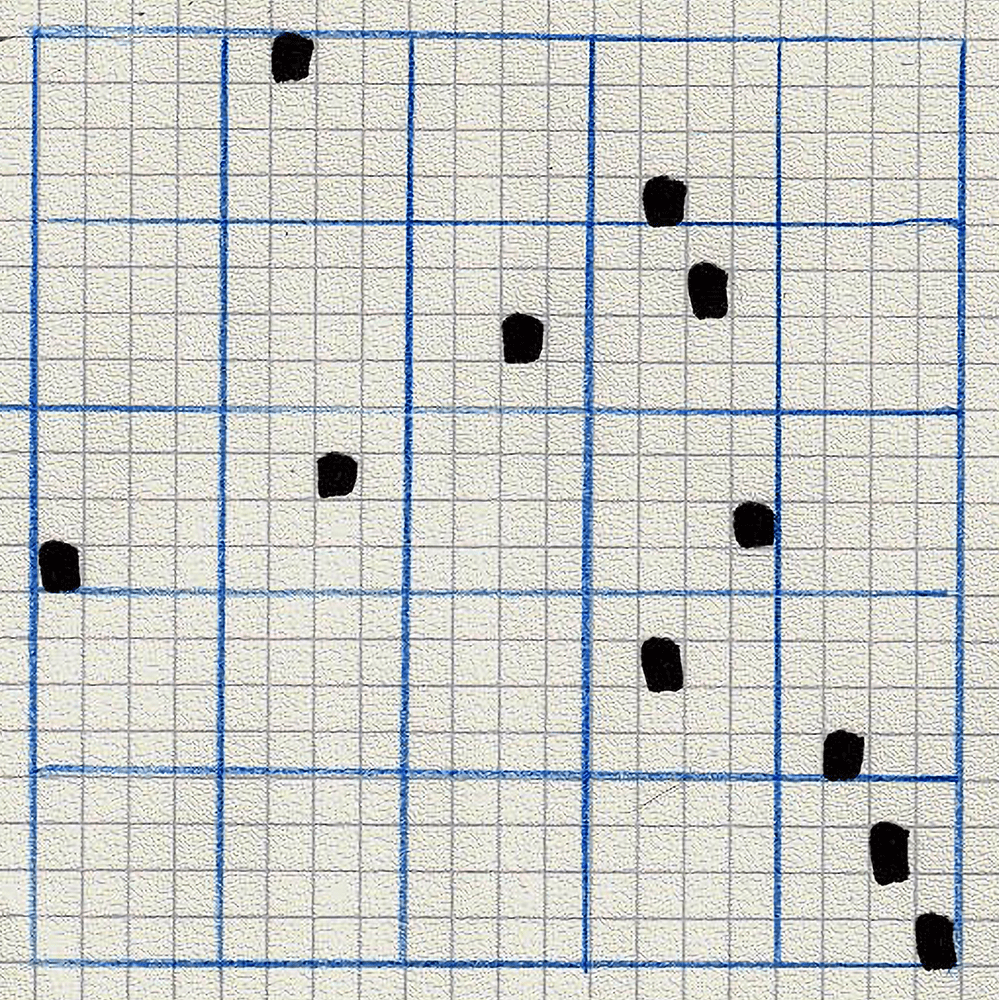

Always interested in astronomy, I tried plotting star constellations on two-dimensional matrix graphs. The coordinates of each star in a constellation could be interpreted as time-point and pitch information, resulting in a complex arpeggiated group of notes. More intriguing was the capability to rotate the map, resulting in many possible variants that stretch or compress the rhythm and chord structure.

The first compositional product of this design work, LIGHTFORMS 1 – Constellations (TC-65), scored for piano, was published by Borik Press in 1992. Naming these patterns, pitch-time chord arpeggios, as constellations became a breakthrough concept

In my book, Mapping the Music Universe, I cite a remarkable pioneer of cartography. “William Smith, a rural surveyor, in 1799 drew a colorful map of the subterranean rock strata of his county in English coal country, launching the modern science of geology.” The map was extraordinary not only as a scientific breakthrough, but also visually by his hand coloring each huge copy.

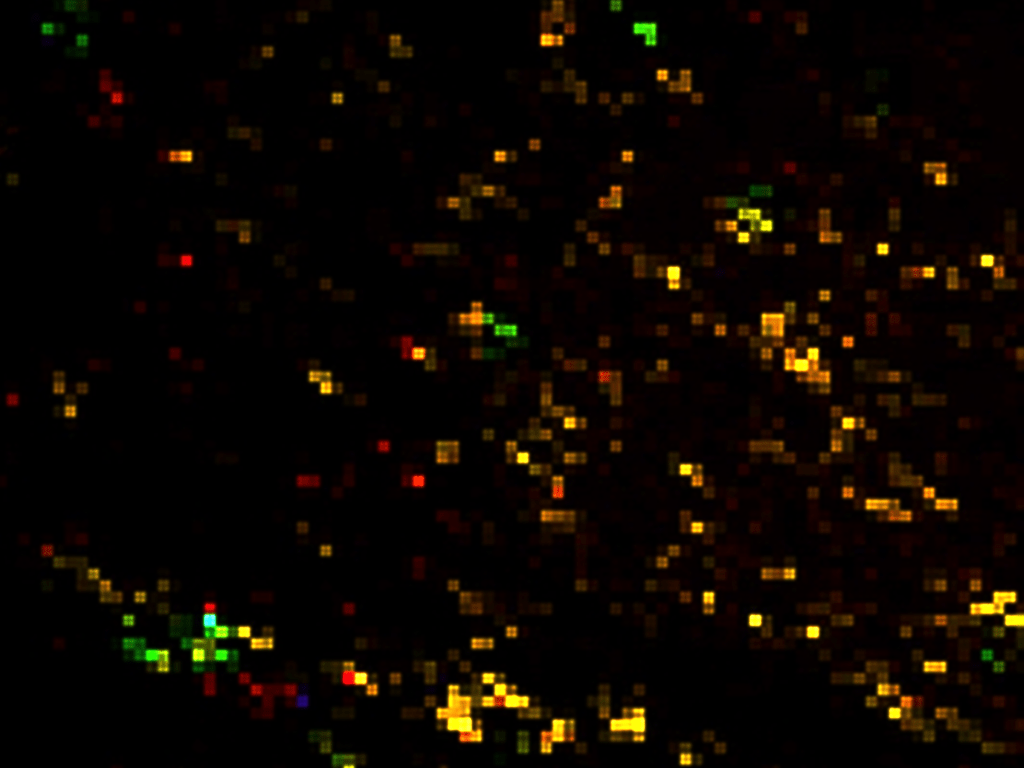

As digital synthesizers came along, sound making with computers offered more calculated control of the timbral (tone color) spectrum. My astronomical metaphor continued with a 1993 piece, using the then state-of-the-art Synclavier II digital synthesizer to “color” the constellation patterns of LIGHTFORMS 1. Reflecting the varied colors of stars, I built color families of sound, distinguishing unique frequency-modulation ratios for each group.

LIGHTFORMS 2: StarSpectra

Clark 1993 (TC-68)

In 1887, French astronomer Amédée Mouchez launched an ambitious international star-mapping project (Carte du Ciel) at the Paris Observatory. It was never finished, until now the challenge has been taken up by the new Vera C. Rubin Observatory (formerly the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope) in Chile. It is conducting the Legacy Survey of Space and Time, repeated astronomical surveys of the entire southern sky.

From wandering forest paths to trekking scenic shorelines, my life has always been full of ambient exploration. Mapping has become my grand metaphor for exploring musical territory, culminating in the book, Mapping the Music Universe. It begins:

“The heavenly motions are nothing

but a continuous song for several voices,

perceived not by the ear but by the intellect,

a figured music that sets landmarks

in the immeasurable flow of time.”

— Galileo Galilei

“When we gaze at stars and planets, they appear as stationary points of light, fixed in place in what seems a random pattern across the entire night sky visible to our hemisphere. Time stands still.

“Throughout human time, humans have imagined that stars make picture patterns we name as constellations: fish, warriors, goddesses, animals. Only the persistent observers, such as astronomers, identify their nightly march across the sky, rising in the east and disappearing below the western horizon.”

In Mapping the Music Universe, a studied journey through musical time, pitch, and structure, many composed examples took on characters of named constellations, galaxies, and galaxy clusters. They coalesced into 12 etudes, collected here as “a continuous song.”

Clark 2021 (TC-114)

Listen, imagining a 24-hour 360º rotation of our earthbound telescope, viewing the entire cosmos in 24 minutes.

_____________