U.Mich. Electronic Music Studio, 1975 —

Mapping the stars —

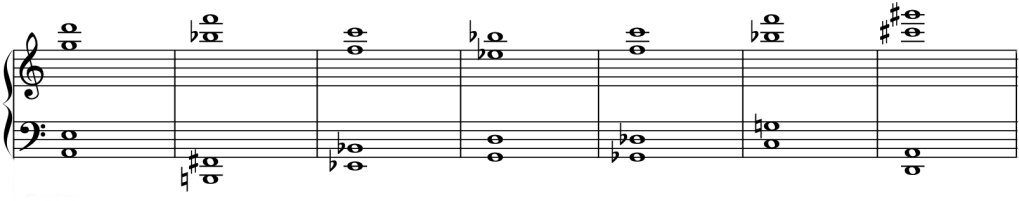

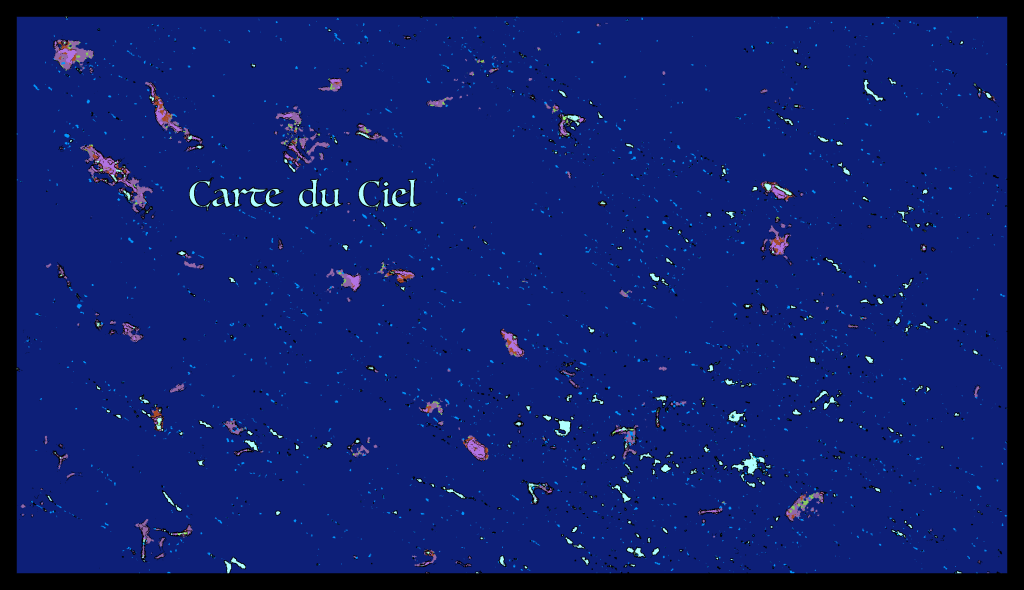

My 2024 book, Mapping the Music Universe, begins with recognition of historic, world-changing pioneers in science and the arts. It includes Carte du Ciel (“Map of the Heavens”), an ambitious second phase of an international star-mapping project initiated in 1887 by Paris Observatory director Amédée Mouchez. A new photographic process revolutionizing the gathering of telescope images inspired the first phase, the Astrographic Catalogue of a dense, whole-sky array of star positions. Carte du Ciel, never completed after 70 years, used the Catalogue as a reference system for a complex survey of the vast field of even fainter images.

In my 2019 computer music of that title, ghostly wisps of sound are punctuated by brighter bursts, clustered in a natural, not-quite randomly dispersed texture.

CARTE DU CIEL

Clark 2019 (TC-98)

Space sounds

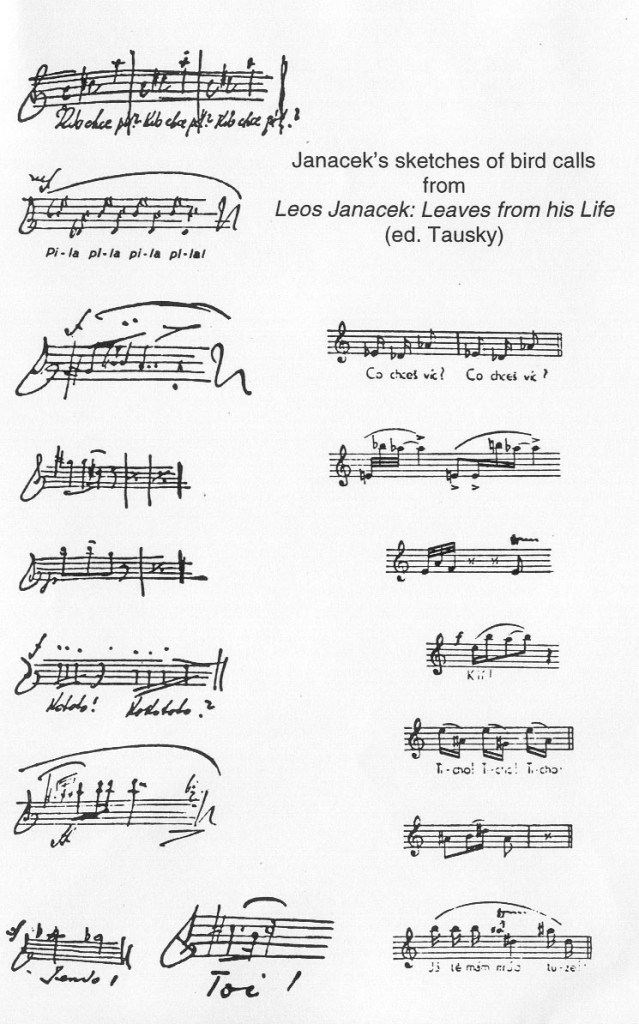

A pioneering work of early electronic music made a huge impact on my imagination when I first heard it on FM radio in the 1960s. Karlheinz Stockhausen made Kontakte (Nr. 12 in the composer’s catalogue of works) in 1958–60 at the Westdeutscher Rundfunk electronic-music studio in Cologne with assistance from Gottfried Michael Koenig. It originated as a tape piece for four-channel loudspeaker reproduction. The title refers to “contacts between various forms of spatial movement” of the sounds coming from four different directions.

Deutsche Grammophon

LISTEN › YouTube

American composer Morton Subotnick’s Silver Apples of the Moon was released by Nonesuch Records in 1967. The title comes from a Yeats poem, “The Song of Wandering Aengus”. It was made with a Buchla 100 analog synthesizer, which Subotnick helped develop, a common practice of early electronic music pioneers to build their own tools.

Part I is a calm exploration of tone quality. Part II generates rapid machine sequences of sounds.

Nonesuch Records

LISTEN › YouTube

Exigencies

My works of analog electronic music were composed at the University of Michigan Electronic Music Studio in Ann Arbor starting in 1975. The studio, on an upper floor behind the stage and organ pipes of historic Hill Auditorium, was assembled by Michigan composition professor George Balch Wilson in 1962.

Patterned after the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center, the studio included reel-to-reel half-inch tape decks running at 15 or 30 inches per second, a mixing board and patch bay, an early model of the famous Moog Synthesizer, other tone generators, and a large wooden coffin containing a heavy metal plate to create electronic reverberation.

Wilson’s first tape piece is an excellent sample of the analog studio’s sound and capability in expert hands.

Equilibrium records

LISTEN › YouTube

My first large work of analog electronic music, Celestial Ceremonies combines otherworldly sounds made with this now antiquated equipment at Wilson’s U.Mich. Electronic Music Studio. (You may hear a resemblance to the sounds of EXIGENCIES.) Updating my work in 2017 with digital enhancements, I also separated out a suite of four sound sketches with subtitles.

Celestial Ceremonies

Clark 1976 (TC-33)

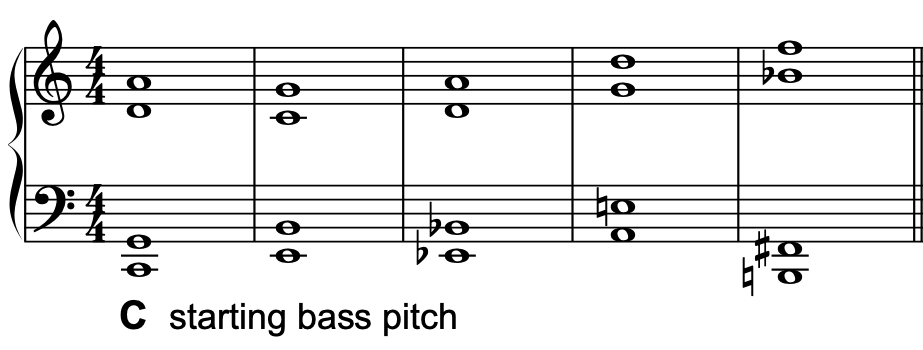

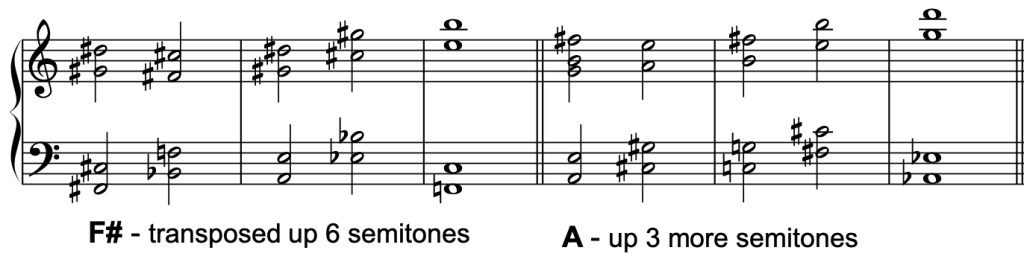

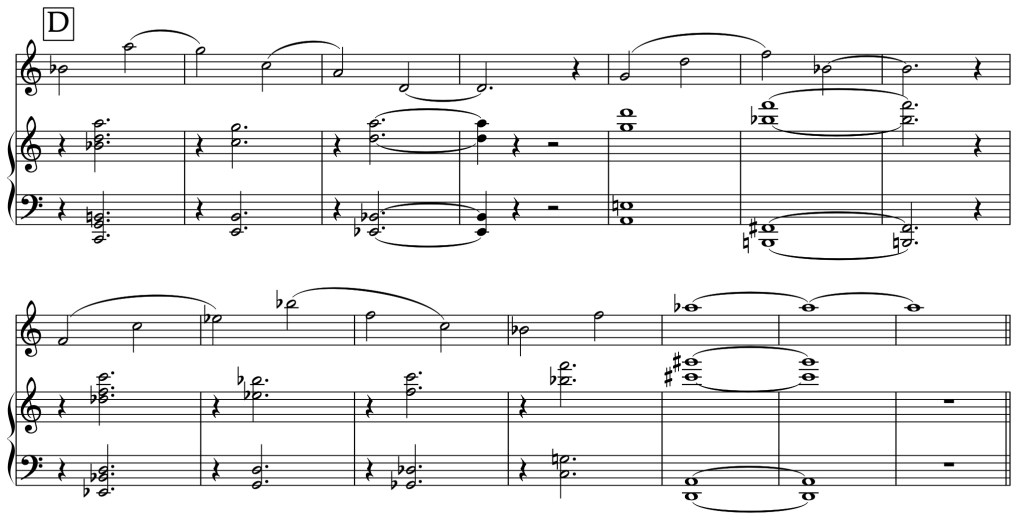

Kraken

For a sample of my current use of digital synthesis technology, we go back to La Mer. Diving into what has been described as our other unexplored frontier, here is a fantasy sketch of the deep sea on the blue planet.

Mar Profundo

Clark 2025 (TC-156)