A sonata is typically a multi-movement piece for solo piano or for an instrument with piano. A shorter form with just three connected sections, the middle slower and quieter, can be called a sonatina. Here is an inside look at how one was composed, step by step. Like the MapLabs in Mapping the Music Universe, this guided tour is in the form of a recipe you can follow to write your own sonata.

Choose a model

I started formal composition study in 1968, first with composer Eugene Kurtz, based in Paris but filling in that semester at the University of Michigan. A proponent of modern French music, his compositional models included Debussy and Ravel. He assigned me to immerse myself in deep study of their music, in particular Ravel’s 1905 work, SONATINE.

I met Beth, a flower lover, in Interlochen in 1975. She had been a promising flute student at Aspen, but was then embarking on a journalism career specializing in horticultural writing.

The Ravel study came back to me later in my career, as I began to adopt its lush, bright harmonic language and a gentle French Impressionist quality. My SONATINE for Beth (2025) brings together the Ravel study, the flute sound, and (in my video version on YouTube) even the flower motif.

Start with a generating idea

The impelling theme can be a melody, a rhythmic pattern, a special kind of chord, or a non-musical image such as a painting or poem.

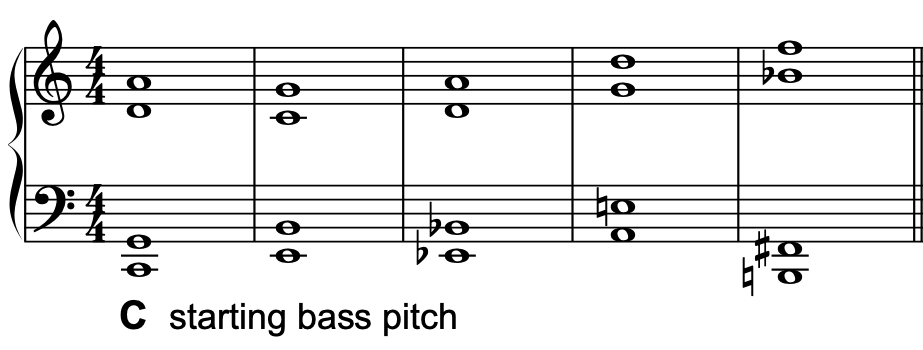

Sonatine for Beth is spun entirely from a single harmonic progression, seven chords, each stacking one Perfect 5th interval above another.

The Perfect 5ths in the two hands are separated by one or more octaves, highlighting this strong interval as a characteristic sound for the piece.

Now some basic tools to develop and vary a generating theme.

Transposition

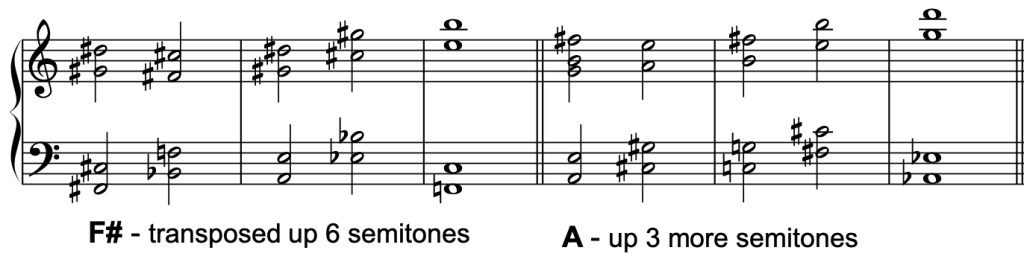

The whole five-chord progression can be transposed. The harmony is heard plainly in a middle section as ten block chords. The last five chords are a transposition of the first five, up three semitones, starting on the bass pitch Eb instead of C.

Sequence is successive statements of a pattern transposed by a consistent interval.

Here is another transposition of the whole ten-chord sequence:

This harmonic material generates melodic lines and many arpeggio patterns, in successive variations of changing register, intensity, and rhythmic pace. Let’s go through the compositional unfolding of this thematic idea.

Extract a melody and bass

Since the starting idea is simply a chord progression, we can select individual tones from each chord for a melody. The most obvious selection is the highest pitch of each chord, even if it is not in a soprano singing range.

At letter A the melody is given a slightly independent rhythm to help set it off from the chords, in addition to the different sound color of the flute. Also, the lower chord tones are articulated one at a time, making a bass line also rhythmically distinct, faster than the half-note chords. (The Bb in the bass line’s first bar is a passing tone, not a chord tone.)

Add arpeggios

An arpeggio is any pattern articulating chord tones one at a time. Usually in order lowest to highest or back down, the individual chord tones can be articulated in any order. At letter A shown above, we already saw the left hand articulate its chord tones one at a time. In the introduction, the right hand is partially broken up into arpeggios.

In the next variation below, right-hand treble chord tones and still some bass chord tones are arpeggiated. Now all three lines (flute, right hand, left hand) have distinct rhythmic patterns, though congruent with each other in the established 4 4 meter.

Next, the flute arpeggiates chord tones in eighth-notes, with the left hand simplified to quarter-notes of two pitches from each chord.

Rhythmic variations

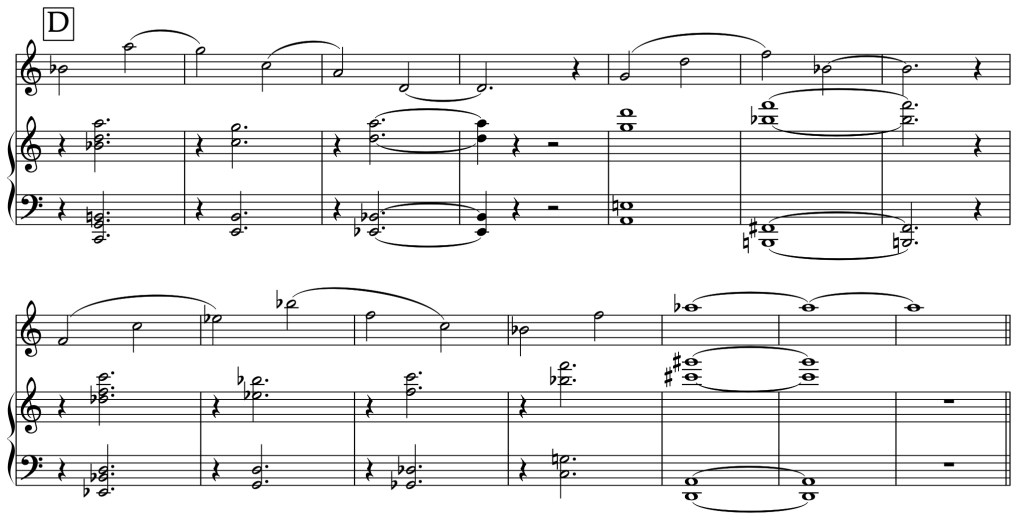

Variation D simplifies the flute melody to just two half-note chord tones per bar.

The two hands reunite rhythmically to place some chords after the downbeat and between flute notes.

Counterpoint

The original term, contrapunctus, translates “point against point” — two or more independent lines interacting in time.

A more active rhythm for the flute line leaves time gaps that can be filled in by another line. The right hand selects chord tones to make a similarly playful rhythmic line that mostly alternates and sometimes lines up with the flute rhythm.

The harmonic progression is still there but just hinted at by the chord tones selected for these interacting lines.

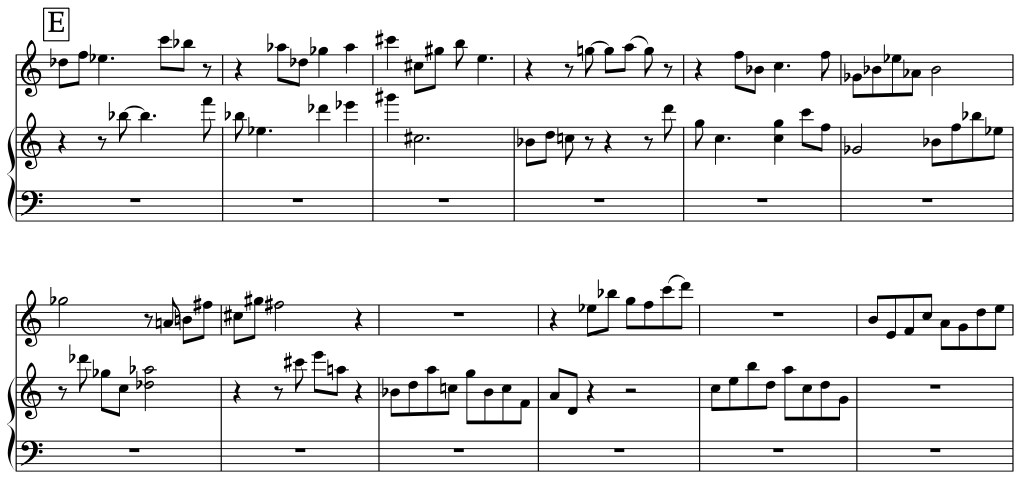

Variation F continues this back-and-forth rhythmic interaction of the flute and piano right hand, now adding back in the left-hand chord-tone pairs with a simple rhythm for a supporting third contrapuntal line.

Texture

Having reached a complex level of three rhythmically interacting, independent contrapuntal lines, a nice contrast will be to simplify. Variation G reduces to a lower-register flute line and only a much simplified skeletal supporting line above it in the right hand.

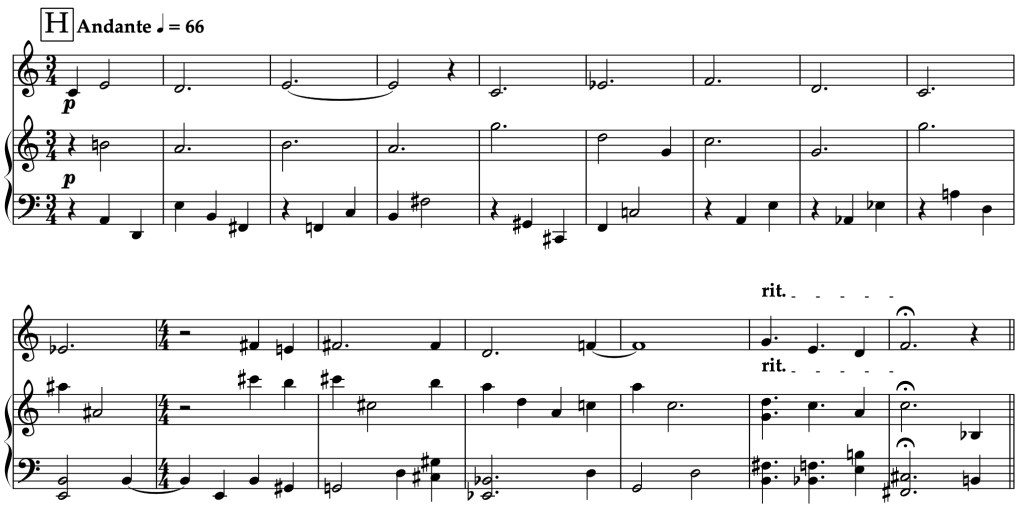

Then the texture begins to revert rhythmically to a simpler alignment of all chord tones.

This paves the way back to a simple piano texture revealing the fundamental thematic chord progression.

Shape a time form

What is the plan for the whole? How will the various versions of the generating idea unfold in the larger time span of the whole piece?

The quiet letter I variation is the apex of an arch form . . .

- starting with simple

- building up more rhythmic and textural complexity

- reaching a stable plateau

- subsiding back to what started it all.

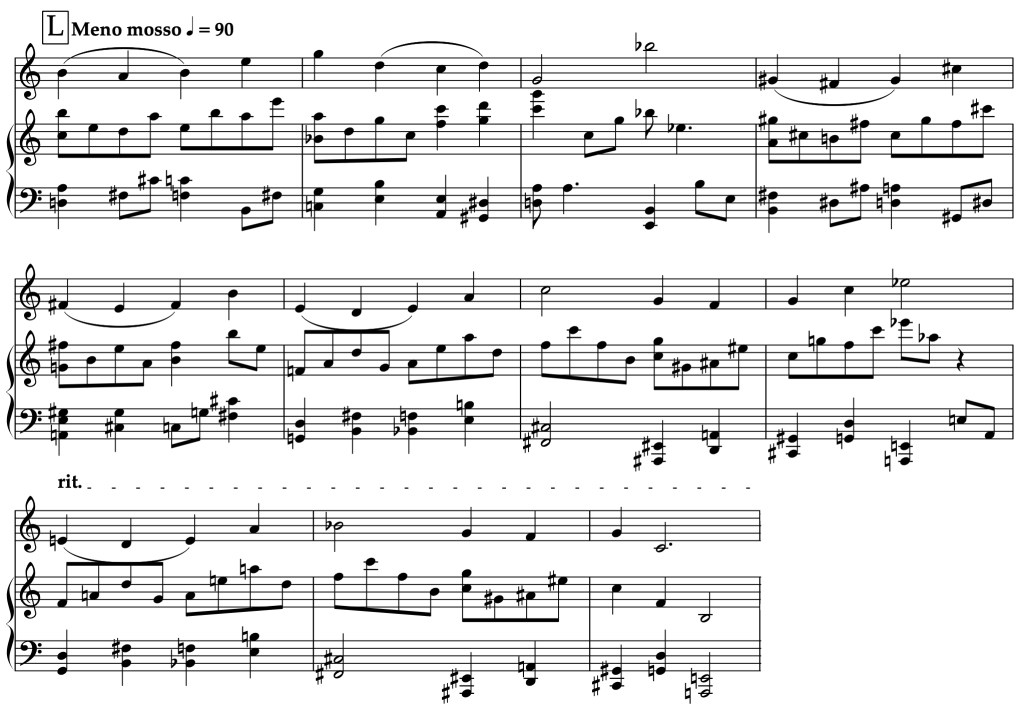

That sets up a recapitulation of the whole process, building up textural complexity again, first with the high two-part counterpoint:

Then with three voices:

Flute line “calming down”:

Coda

A good essay ends with a conclusion or a summary restatement of the thesis.

Our musical coda summarizes with a last return to the beginning. The chords are back to their very low and very high registers. The flute makes a small melodic arch, ascending to the pitch B, then climbing down gently to its lowest possible pitch, C.

Fine

A final edit and audit are mandatory. In the case of our example, listening revealed that the beginning needed a piano introduction with some rhythmic vitality. Some sections were also reordered to improve the flow. Thus, the piece will not begin with a plain statement of the progression, and there will be a somewhat different order of other events.

Now listen to the whole 6-minute parade of variations on a single chord progression.