This lab will pursue several learning objectives:

- scoring for a chamber trio of three different instruments

- classic ternary form

- building a twelve-tone series of trichords to mold a personal tonality

Arnold Schoenberg’s famous twelve-tone row technique, devised in the early 20th century, prescribed a method many composers adopted for regimenting and streamlining choice of pitches in the otherwise seemingly unlimited forest of the chromatic scale’s 12 scale steps — what theorists later called the aggregate collection of all 12 pitch classes. Music composed in this manner came to be categorized as “atonal,” despite the fact that a particular 12-tone row defines what Perle would call a unique 12-tone tonality.

The so-called atonal music was complex and mostly dark and dissonant. Can a technique like this also be used to methodically create coherent tonal characters of brighter, simpler sonority?

1. Choose a model

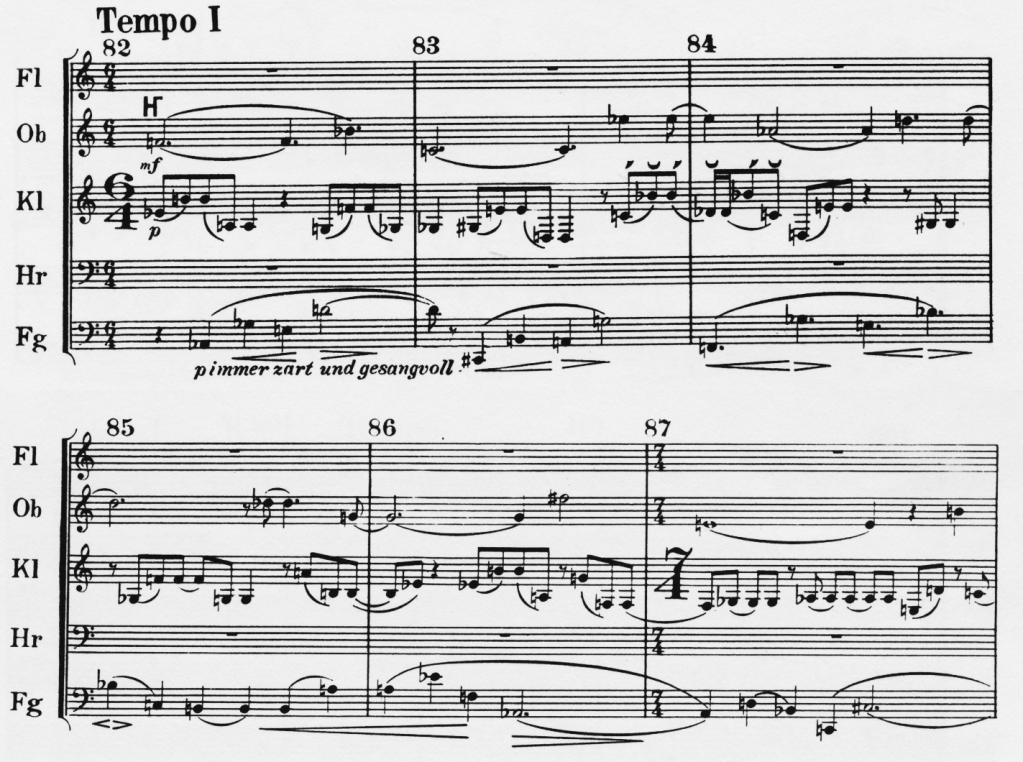

One of my favorite 12-tone pieces is Schoenberg’s Wind Quintet, Op. 26. Premiered in 1924 on Schoenberg’s fiftieth birthday, it was dedicated to Schoenberg’s young grandson Arnold. In four movements, it has a graceful neo-classical Viennese quality. It also is historically only the second piece ever (after his Suite for Piano, Op. 25) composed with Schoenberg’s new 12-tone row technique.

The slow third movement, tempo marked “Etwas langsam,” displays a clear use of a 12-tone row in graceful counterpoint between the five instruments. The facile scoring of these instruments explores textures ranging from isolated solo to duos, trios, and even dense five-part counterpoint.

2. Design a 12-tone series

I imagine the typical way composers design a 12-tone row is by writing a line, choosing the interval from one pitch class to the next while not reusing any pitch class, until all 12 are included. That leads readily to a linear, contrapuntal approach.

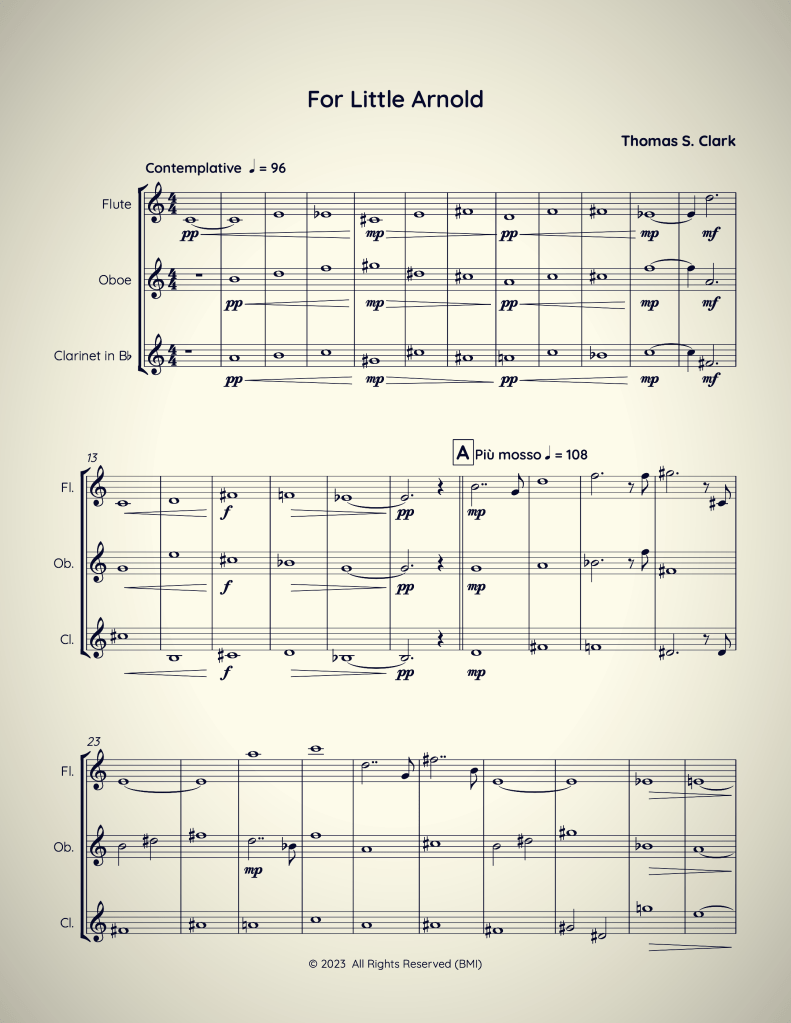

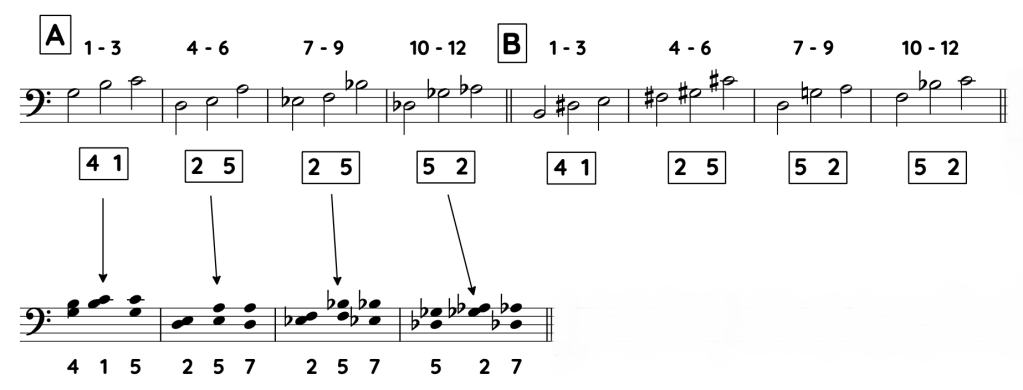

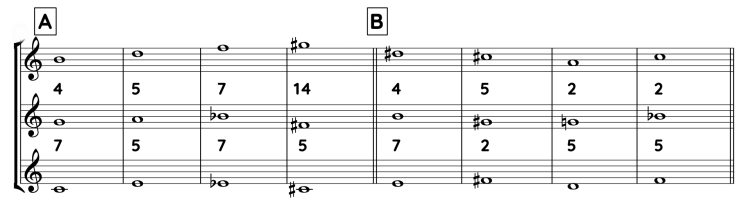

For our example in this lab, we’ll work instead with trichords, each a group of three pitch classes making a three-note array and set of three intervals. Here is such a row (A) and a slight variation of it (B):

The A version also shows the three intervals in each trichord.

Note that the 2 5 and 5 2 scale patterns are the same, representing a set that is inversionally symmetrical. (That is not true of 4 1 and its unique inversion, 1 4.) Its complete-octave array is 2 5 5. Think of it as a circle of the twelve semitones in an octave. Unwinding the circle through octaves looks like: 2 5 5 2 5 5 2 5 5 2 . . . etc. This is a palindrome, reading backwards the same as forwards.

Here is a voicing into 3-voice chords:

You can see (and hear) that the voiced-out trichords can make constellations predominantly of 5-semitone and 7-semitone intervals. This is what makes the sound of the progression coherent and somewhat more like Copland than Schoenberg in character.

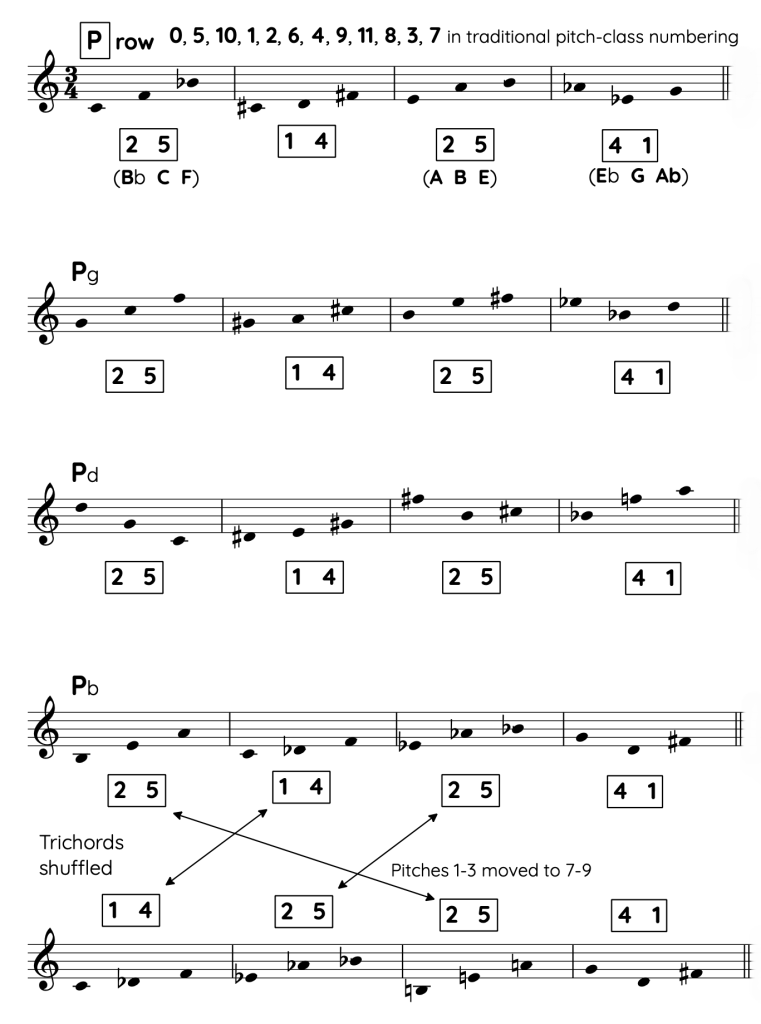

3. Twelve-tone rows

Now we can delve into the linear potential of the series we’ve constructed. I’ll call my principal row P in keeping with standard theory, designating the transposition by the name of the starting pitch class. (Standard theory uses pitch class numbers — C = 0 — to designate the starting pitch.)

Serial technique is just a box of 12-tone tools, which you can use in any way you wish. For the last row above, I shuffled the order of the trichords. The shuffle puts the trichords inside out, with the 1 4 array now at the beginning. This gives me more options when building counterpoint between two lines with each its own row form. Like rearranging four toy blocks, the shuffling still builds a 12-tone aggregate collection no matter the order of trichords or pitches within the trichords.

4. Imitative lines

As we observed earlier in Opus 26, a row is a natural material for building contrapuntal lines that are similar in interval shape. When these similar shapes are reinforced with similar or identical rhythmic patterns, the lines mimic each other in their back-and-forth conversation.

5. Ternary form

Of all the classic form models, ternary is one of the simplest in concept and strongest to perceive. Opening material is contrasted with a middle section of different tempo, texture, register, rhythmic pace, etc., followed by a return to the opening material: A B A. (Several familiar classic model forms are ternary, including Sonata Allegro, Da Capo Aria, and Minuet and Trio.) Often the returning opening material of the third section is embellished or varied in some way while not clouding recognition that it is a recurrence of the opening.

For Schoenberg’s Etwas langsam third movement of the Wind Quintet, the opening material consists of two-part counterpoint between horn, marked as the Hauptstimme preeminent line, and bassoon (Fg) marked as the Nebenstimme subordinate line.

Opus 26 middle section is faster flowing, with much more rapid, complex rhythms in a denser four-part counterpoint:

The third section brings back but alters the opening’s two lines, moved from horn and bassoon to oboe and bassoon, with the addition of a third contrapuntal voice in the clarinet.

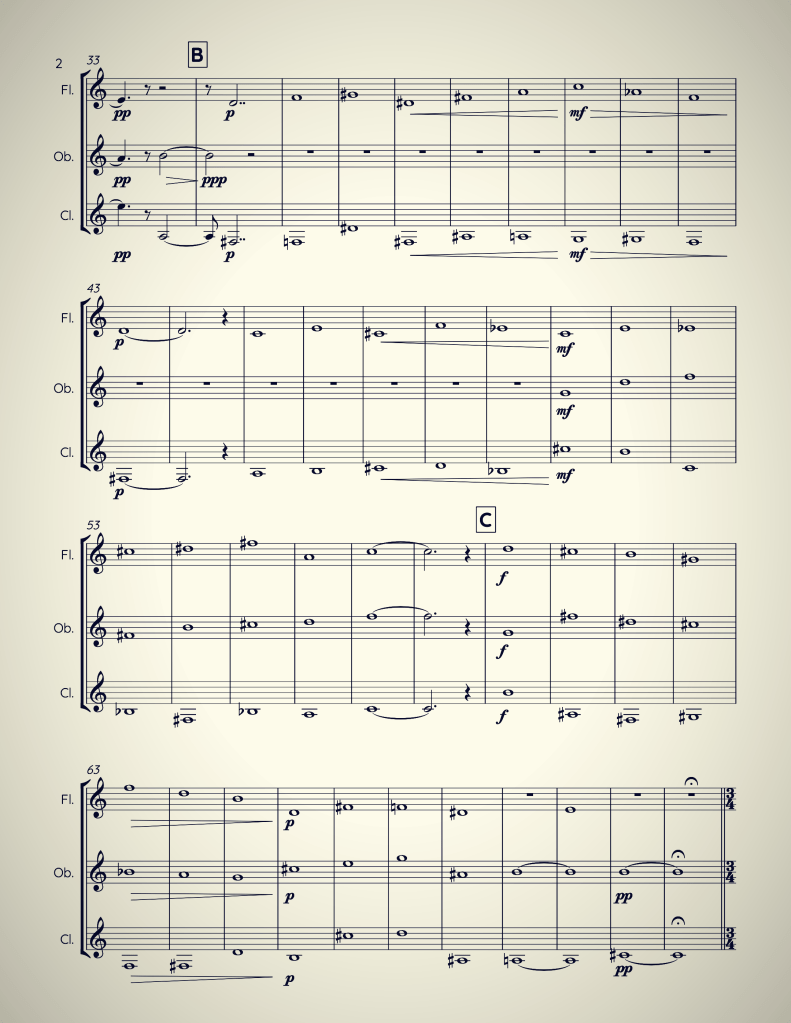

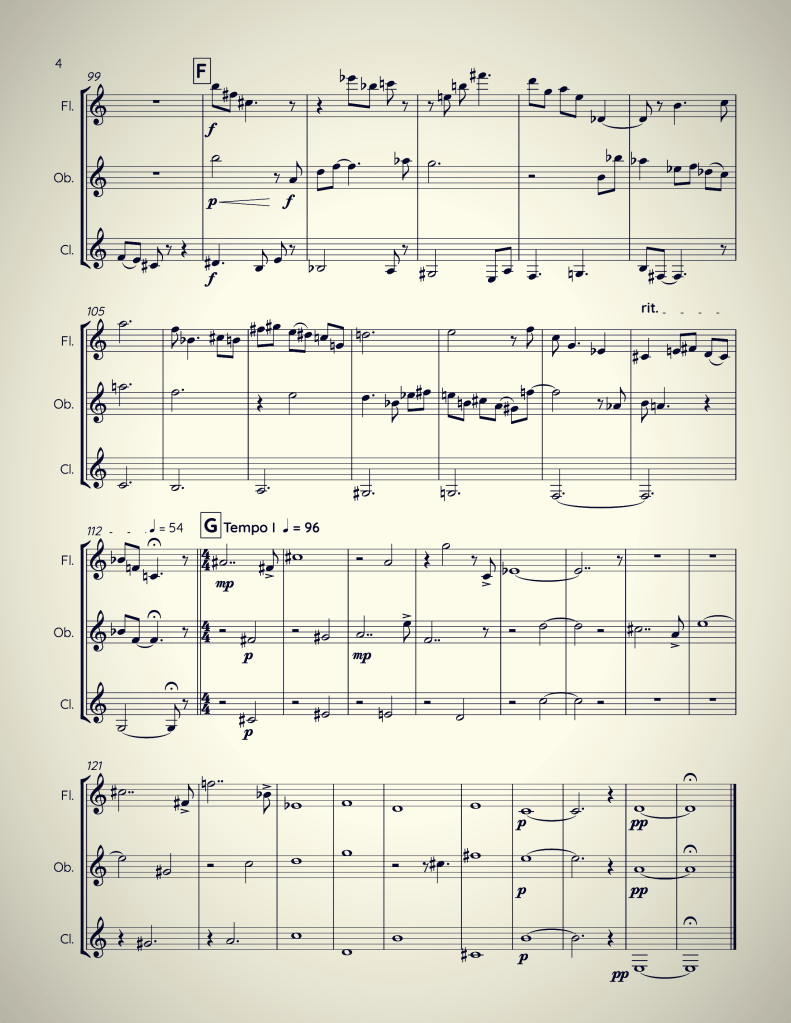

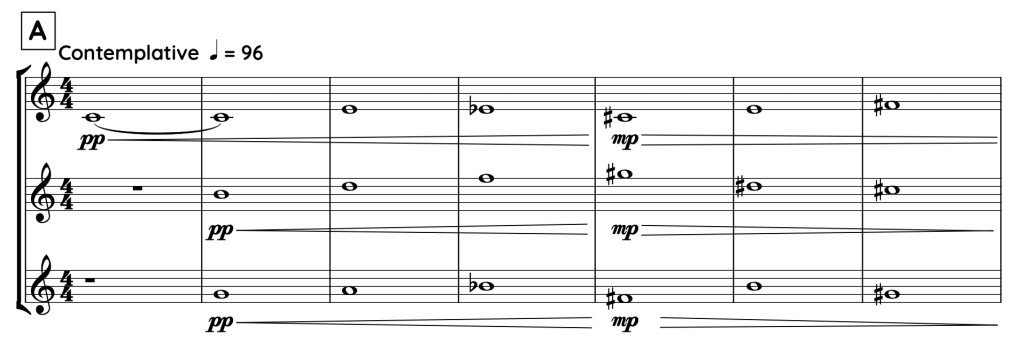

For our MapLab example, the chorale-like chordal setting of the trichords we’ve already seen will be the serene opening and ending material. Imitative contrapuntal setting of the row in a faster tempo and much faster pace make the contrasting middle. (Many classic three-part forms, by the way, are the converse, fast – slow – fast.)

Opening:

The opening material continues with a variation of the chords, transposing them and adding rhythmic interest with single 8th-notes each arpeggiating a pitch of the chord.

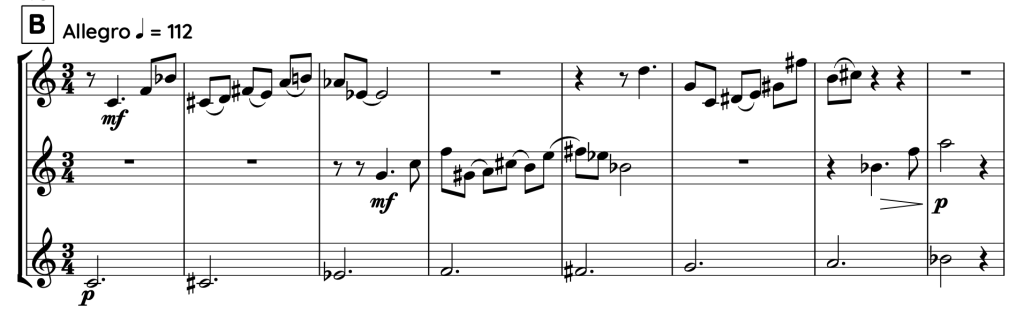

Contrasting middle:

Note: if you’re wondering how I pulled the lower line of dotted-half-note steps from the row, I didn’t. It is free counterpoint for a simple supporting “bass line.” Those pitches are drawn from the trichords expressed above them, as unison or octave “doubling” of single pitches from the upper lines.

The recap first brings back the opening’s single-8th-note arpeggiations then proceeds back to the still chords of the very beginning.

6. Scoring the trio

For this lab, choose any three different instruments. They can be in the same instrument family, like a brass trio of trumpet, horn, and trombone. Or it can mix instruments from different families, like flute, horn, and cello. You can guess from the audio above, I choose a woodwind trio of flute, oboe, and Bb clarinet.

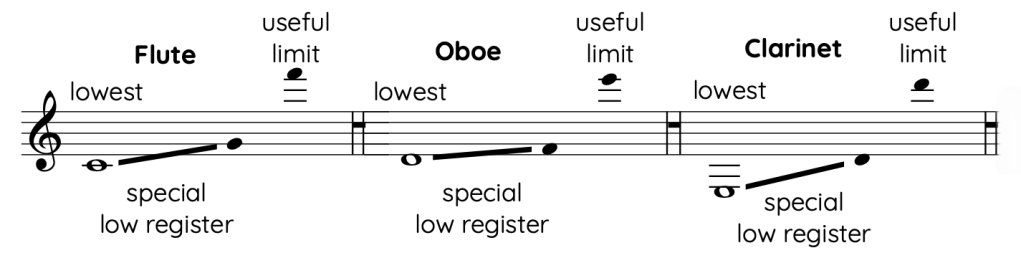

Get to know your chosen instruments, not only their overall range but also the particular characteristics of sub-registers. For orchestral string instruments, it is good to know their open string tunings and recognize those strings’ different qualities; the lowest string of each instrument is thicker and produces a thicker, grittier timbre. For my chosen three, flute and clarinet have wonderfully rich, dark lower registers, while the lowest few pitches of the oboe’s range are squawky. Each of the three instruments have upper ranges that thin a bit in timbre but can be elegant or powerful.

My scoring will emphasize use of those rich low registers of the flute and clarinet. Many chords will be voiced with oboe on top, flute in the middle, and clarinet lowest. Nonetheless, the score will show them in standard score order with flute at the top. Also, the clarinet is a Bb transposing instrument. That means in the score and player’s part, a written C will sound one whole step lower as a concert Bb. When I want, say, an F to sound, the clarinet part will show a written pitch one whole step higher, G.

For a well-balanced chamber-music trio should balance how much time each instrument gets as the active, preeminent voice in the texture (which Schoenberg would call the Hauptstimme).

7. Finished score

Tempo and dynamics are essential to vividly portray where the music is going — launching, growing, swelling, subsiding, approaching a cadence or climax. Articulation marks will be particular to each instrument type. Rehearsal letters or measure numbers will be helpful in rehearsal.

Since my finished example has a childlike playful curiosity, its title follows Schoenberg’s Opus 26 dedication to his grandson. Imagine a child in a sunny garden.

For Little Arnold